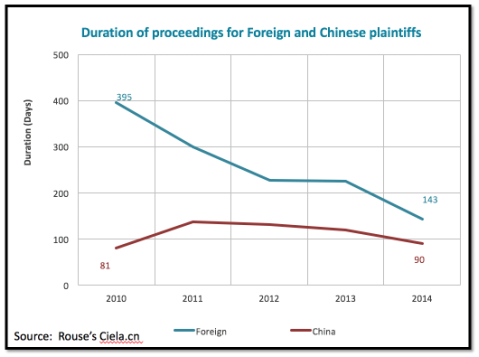

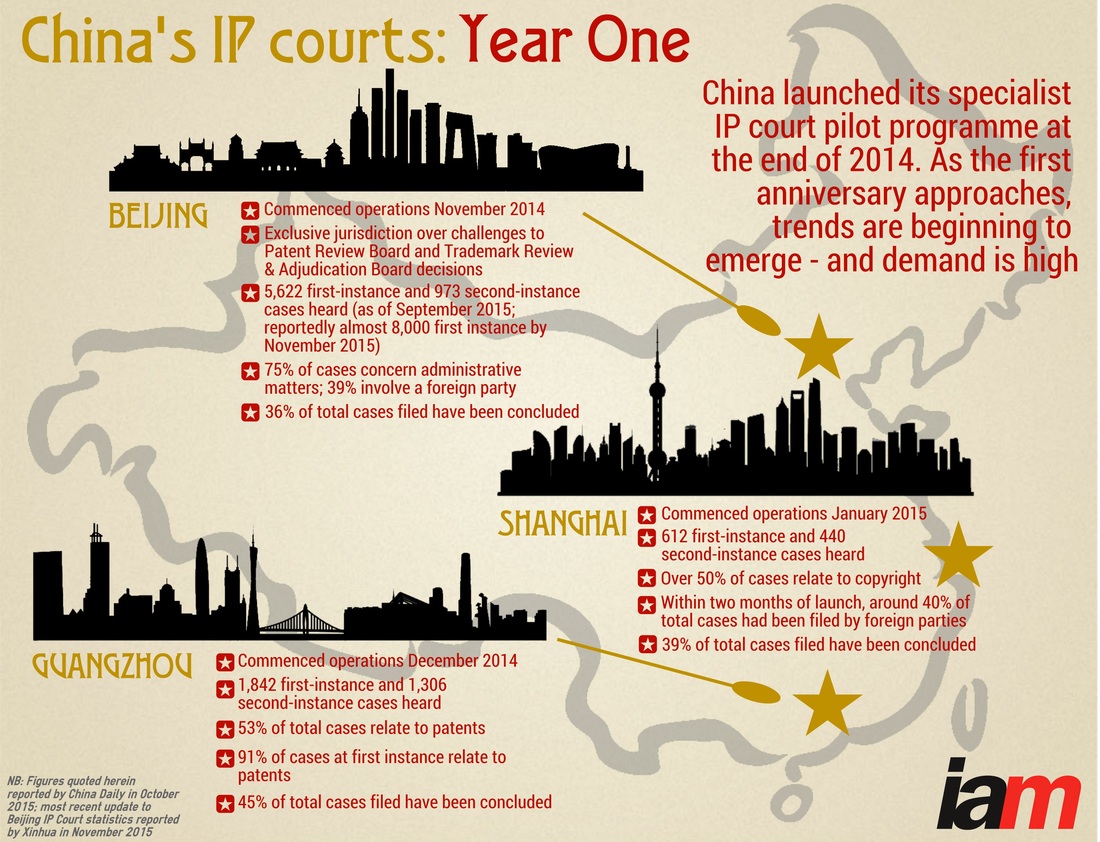

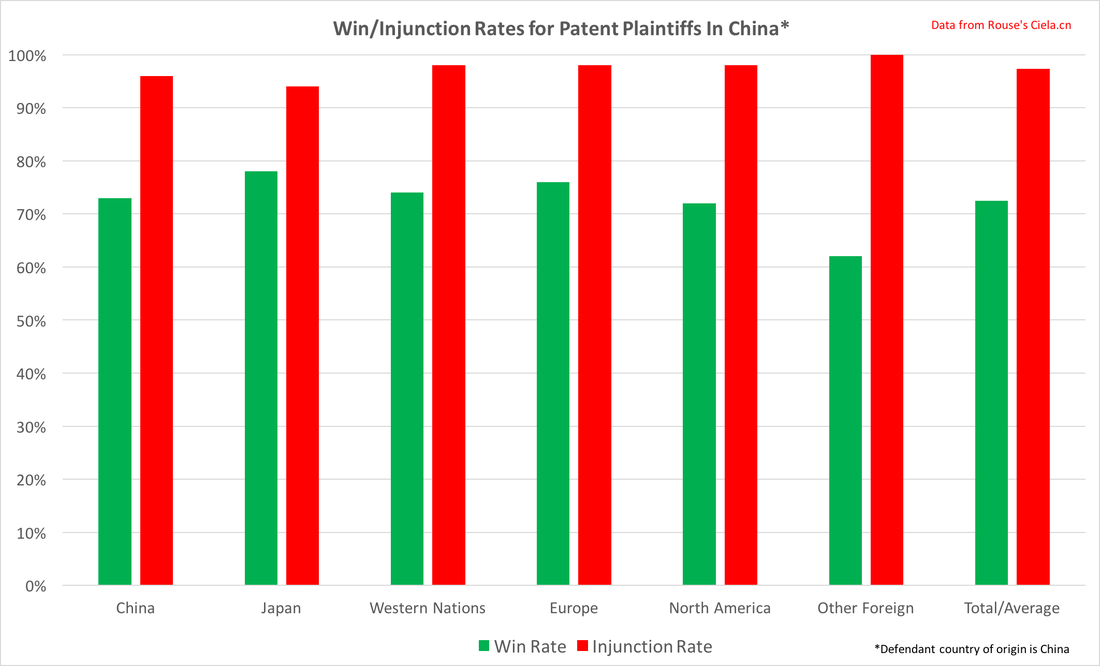

My Financial Times Article: "Foreign Companies Must Learn That Trust and Respect Are Paramount"11/23/2015  Originally published at http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/b109e25c-87ce-11e5-90de-f44762bf9896.html#axzz3sIWMw2AI and reprinted with permission. Click here for the hard copy version. China’s economic and industrial transformation is occurring so rapidly that foreign companies often fail to appreciate the risks of doing business in the country. This is particularly true in the sphere of intellectual property (IP), where companies now enjoy much greater protections but have simultaneously been tripped up by competition regulators’ increased scrutiny of their patent and licensing practices. China’s ability to protect patents has grown after decades of non-existence and non-enforcement. In 10 years, the number of patent litigations filed has more than quadrupled, with close to 10,000 cases submitted last year. The Chinese government’s new specialised IP courts now provide companies with an enforcement mechanism comparable to, if not better than, those in Europe and the US. Litigation in China also offers many advantages to patent owners, including win rates above 75 per cent (and even higher for foreign patentees), injunction rates above 95 per cent, short time to trial, scant discovery and low costs (less than one-tenth of those incurred in the US). Most importantly, because so many supply chains pass through China, a single litigation can effectively impose a global ban on sales of a disputed product. But not all patent owners should rejoice. Along with a strengthening of the patent system has come increased enforcement of China’s 2008 Anti-Monopoly Law (AML). Over the past three years, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has beefed up staffing levels and raised its price-related investigations fourfold. In 2013, the NDRC imposed price-fixing fines of Rmb353m on six Korean and Taiwanese LCD panel manufacturers. Last year the NDRC began investigating InterDigital, a US wireless technology company, after complaints by Chinese companies. InterDigital subsequently reached settlement agreements with the Chinese complainants and, in an undertaking with the NDRC, said it would scale back the royalty rates it charges. The NDRC also probed US technology giant Qualcomm on similar grounds and, earlier this year, imposed a record penalty of Rmb6.1bn. Qualcomm agreed to stop some of its “patent bundling” practices and lowered certain royalty rates by one-third. AML penalties and fines in China can be extreme. But in the case of Qualcomm, perhaps the worst consequence of its run-in with the NDRC was the separate antitrust inquiries that followed in South Korea, the European Union and US. There are a number of steps that companies can take to minimise the risks posed by regulatory investigations. First, companies must have friends in China. In a country where everything is based on relationships, every company must have multiple levels of relationships with both government officials and influential Chinese industry leaders who have their ear to the ground. This is not to encourage any type of corruption, but rather facilitate a free flow of information. In China, trust and respect are paramount and cannot be developed overnight. The challenge to Qualcomm might have been avoided or minimised if the US company had had better Chinese government contacts who could have advised it that problems were brewing and explained the need for action. It is at this sort of early stage that having knowledge of the problem and the ability to communicate a defence is paramount. Once the investigation was announced publicly in February 2014, there was no path for the NDRC to impose either a minimal penalty or no penalty without losing face. Had Qualcomm and NDRC instead been able to negotiate a mutually acceptable solution earlier — and with less publicity — the result may well have been a lesser penalty that did not trigger follow-up investigations in other jurisdictions. Second, all foreign companies and their executives, lawyers and other agents must act with great respect in dealing with Chinese officials. US companies in particular have a well-deserved reputation for lacking deference and humility. Had InterDigital and Qualcomm originally approached their situations with greater meekness, things might have evolved quite differently. Often it is the lawyers that get in the way, because when you are a hammer everything looks like a nail. The better road is one of calm and thoughtfulness rather than agitation and hostility. Third, any company that licenses patents or technology in China should always have in its back pocket a specific minimum acceptable royalty rate. That way any dispute can be nipped in the bud with a public announcement that the company is lowering its licensing rate to an “even fairer level”, with examples to support this claim. This is not ideal but far better than the alternative of having to face a formal AML investigation. The writer is chief patent counsel for an international law firm specialising in intellectual property, and a former Qualcomm lawyer.  IAM just posted this graphic indicating the amazing activity at the specialized IP courts in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou have been. Interestingly, IAM states that within two months of launch, the court in Shanghai, 40% of cases had been filed by foreign plaintiffs, with US companies filing most of these. My firm maintains an excellent database of Chinese filings at Ciela.cn, and the data show that foreign plaintiffs are more successful than Chinese plaintiffs both in terms of win rate and damages amount. In particular, over the past five years, win rates for foreign plaintiffs surpass Chinese plaintiffs 71% to 65%. Although foreign plaintiffs are likely to undertake more diligence than Chinese companies before filing against Chinese companies in China so that these cases are effectively pre-screened, there remains no evidence to suspect judicial bias towards Chinese companies. Also, for Chinese vs. Chinese cases, there is a statutory 6-month time limit for filing to trial. For foreign-related cases, there is no time limit on proceedings, but the length has been cut by almost two-thirds for foreign plaintiffs and now approaches the length of time for Chinese parties.  Although there are still relatively few foreign vs. Chinese cases, and even fewer foreign vs. foreign cases, because of the many advantages of the Chinese enforcement system and of the ability to obtain an injunction against sales in and export from China, both types of cases are growing. And importantly, as long as foreign parties follow the rules and do the right thing (the subject of a coming post), foreign plaintiffs get a fair shake in cases in China.  Introduction Blaming China for America’s economic problems is a familiar refrain. In particular, it is popular to accuse China of not respecting IP rights. Although this has been a legitimate accusation in the past, over the last five years or so, the winds of change have blown. In fact, China has emphasized patent rights much more than the US, and created a competitive patent enforcement system that rivals any in the world. Considering the strategic importance of the Chinese business market, China is now arguably the most effective place to enforce patents anywhere. This article provides an overview of how the US has weakened patents, and then explains the genesis of patent rights in China and how the Chinese government has delivered a competitive patent enforcement mechanism in a short time. China may be the new (very) Eastern District of Texas. The Degradation of Patent Rights in the US US court decisions, laws, and even Presidential actions have been eroding patent rights for several years. Starting with eBay in 2006, when the Supreme Court eliminated injunctive relief for most patentees, to courts making damages more difficult to prove, to the consistent attack on software patents via CLS Bank and other cases, to liberalization of awarding of attorney fees in failed cases, US courts from the top down have made life increasingly difficult for patentees. Patentees cannot even readily contact parties they believe infringe their patents without triggering declaratory judgment jurisdiction. In addition to court decisions, the America Invents Act (“AIA”) created new post-grant opposition procedures through the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB.”) These procedures have effectively destroyed the longstanding presumption of validity that issued patents have traditionally enjoyed. In fact, former Federal Circuit Chief Judge Randall Rader has called the PTAB a patent “death squad” because the PTAB has found nearly three-quarters of challenged claims unpatentable. Perhaps the most noteworthy example from an international perspective was the 2013 Presidential “veto” of a U.S. International Trade Commission (“ITC”) exclusion order banning import of Apple’s iPhones and iPads found by the ITC to infringe Samsung patents. The last time similar Presidential action had been used prior to this was 1987.[1] Whether the fact that the patentee was a Korean company and the proven infringer a US technology darling had anything to do with this decision matters little. Perception, particularly internationally, is that the US is a hypocrite demanding other countries respect US intellectual property while not itself respecting IP rights. This has led to devaluation of patents in the US, including fewer patent sales, lower average value, and fewer patent lawsuits – especially when corrected for the fact that now patentee much generally sue defendants in separate suits as required under the AIA. Further, time to trial continues to increase while average damages decrease. All this means that it is harder to enforce patents these days in the US, and even when you can, the reward is lower. The Rise of Patent Rights in China Contrary to the steady decline of patent rights in the US, China has been building up the importance and value of IP in general, and patents specifically. Fifteen years ago, the Chinese civil court system was not easily accessible by Chinese citizens and businesses, much less foreigners. The patent enforcement scheme was even worse. However, since that time, China has steadily developed patent enforcement mechanisms comparable to the US and Europe. China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, and became a member of the TRIPS agreement the same year. The Chinese Patent Law, originally enacted in 1984, has been revised in 1992, 2000, and 2009, with each revision including vast improvements. In April 2015, draft amendments were published for comment, with likely enactment in mid-2016. Even more important than the evolution of patent law itself has been the progress of the Chinese court system to improve patent enforcement. For example, in 2014, China created specialized IP courts in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. What has resulted is a combination of the tactical advantages of the US International Trade Commission, Germany, the Eastern District of Texas. Why China is Now a Top Patent Litigation Forum: Law and Business The judges adjudicating patent disputes are educated, knowledgeable, and professional. Further, those judges without a scientific background often use technical advisors to assist with complicated technology issues. Most importantly, because these judges hear only IP cases, they are becoming better at handling technical patent cases. While monetary damages remain low compared to US proceedings, this, too, is changing as judges become more assured in their decisions. Although China is a civil law system, the IP judges in particular are actively aware of other courts’ decisions. The practical effect is that unless you file against a government-controlled entity, prior decisions are likely to be quite persuasive. In addition to good judges and specialized courts, China now boasts a very short time from filing to trial and judgment. For example, time from filing acceptance to trial in Chinese patent cases is mandated by law to be no more than six months for domestic litigants. Although this deadline does not apply if foreign litigants are involved, most cases reach the “first instance” (same as a judgment in US case) by 6-12 months. Further, unlike the US, where injunctions are the exception, in China the 95% of winning parties receive an injunction. Also, similar to the German model, Chinese courts allow sparse discovery. Being ready to try your case on the day filed is simply good practice because it puts the defendant on their heels from the start, never allowing them to catch up. China rewards such preparation, through the lack of discovery and fast track to trial. Plus, every stage of the case is faster, leading to a much lower cost of litigation – in many cases one-tenth the cost (or less). Another advantage for patent owners regards validity challenges. In contrast to the US, in China the validity of a patent is not challenged in a court, but is challenged exclusively through invalidation proceedings before the Patent Reexamination Board of the State Intellectual Property Office. Usually the time required to challenge validity is longer – often much longer – than it takes to get a judgment and injunction. Importantly, there is no retroactive effect on any infringement decision from later invalidation. Therefore, patentees can create tremendous leverage by obtaining an injunction while the invalidity case remains pending. Further, according to statistics from CIELA.cn, a Chinese patent litigation database designed and managed by the Rouse law firm, validity is challenged in less than 15% of cases. Comparing this to the U.S. system, in which validity is nearly always challenged in court – and increasingly through reexamination proceedings as well – China provides not just an easier path for patent owners in Chinese litigation, but also a more affordable one. In many areas of technology, preventing an adversary from selling their product in China, the world’s second largest market, for even a few months can be devastating. But it is more significant than that. Because so many of today’s products are not just sold in China, but also made there, an injunction can effectively shut down worldwide manufacturing and sales for 6-12 months, even if the patent is subsequently found invalid. Even though damages are still relatively low (although we are now seeing some awards in the tens of millions of dollars), an injunction is what provokes huge settlements – which are not counted in statistics. Finally, win rates for patentees hover around 75% (I am going to brag and note that my firm has a 95% win rate).[2] Interestingly, win rates for foreign patentees are generally higher than for domestic patentees. Challenges of Litigating in China Although there is a lot to like for patent owners, China has a vastly different culture. This translates to different rules and behaviors in the adjudication of patents. Unlike litigation in the US these days, lawyers must always show respect, and behave honorably. Further, like the Eastern District of Texas, it is good to have someone on your team that “goes fishing with the judge.” This is not to say that anything is corrupt, but that it is always better to know the judge, especially when he, not a jury, will be making the decisions. Smart litigants will hire top Chinese lawyers, which are sometimes difficult to find. Not because they do not exist, but because Americans and other Westerners cannot effectively evaluate Chinese lawyers and firms. Further, even if the lawyers are substantively and technically acceptable, Western in-house counsel and business executives are likely to be dismayed by the typical level of service. In China, it is difficult to find lawyers that will preemptively explain how the case is going and provide the opportunity for company lawyers and business leaders to provide input. Many Chinese lawyers only respond to questions without being proactive in any way. There are a several of ways to cope with this. First, you can just hire a Chinese firm that has a good reputation based on what you can find on the topic. This is problematic for the reasons above: namely you cannot know what you are getting in terms of quality, and the level of service and responsiveness is likely to be low. Second, you can hire a large Western corporate law firm. There are now plenty of offices of Western firms to be found in China. The problem is that most are merely outposts with just a few lawyers and do not specialize in IP (and even if they do, the Western lawyers have no real patent or technical expertise, or trial experience in the US, much less China). The people who manage the case will be very expensive partners who will merely outsource the principal work to the same Chinese firms that may not be particularly effective. While the Western lawyers will be happy to talk about their view of the case for $1,000 an hour, their view is likely not particularly well-informed or predictive of any result. This is because unless they are truly a part of the litigation team, speaking with the Chinese lawyers every day, the Western lawyers just cannot provide much other than a large bill added onto the service of a Chinese legal team of unpredictable quality. Finally, perhaps the best model, and one that has been slow to grow simply because it is not as profitable for the law firm, is a fusion of the two above: a firm that has experienced Western patent litigators working integrally with Chinese patent trial lawyers providing top-notch service, while also providing excellent substantive legal work at a reasonable cost. Conclusion Intellectual property, and patents in particular, are now a central facet of China's national strategy as it strives to become an innovation-driven economy. In a brief period – barely over a decade – China has created from whole cloth an enforcement system on par with, or better than, systems around the world. While patent rights in the United States continue to deteriorate, China is moving in the opposite direction. China is now the second largest economy worldwide and still growing. Any reasonably sized US company must engage in China to compete in the world market. The good news is that China’s IP system is catching up just in time. [1] Ironically, this time it was Samsung on the winning end against Texas Instruments. See Certain Dynamic Random Access Memories, Components Thereof and Products Containing Same, Inv. No. 337-TA-242, USITC Pub. 2034 (Nov. 1987). [2] Such statistics can be easily calculated via my firm’s Chinese patent litigation statistical tool at CIELA.cn. This tool can be used to determine, among other things, which court has highest average damages, the average injunction rate for each court, which courts are more friendly to foreign entities, and which courts are running more quickly. Note: This article was originally published by Portfolio Media, Inc. and IP Law360 and has been reposted here with permission. The original article is available at http://www.law360.com/articles/717562/china-increasing-patent-rights-as-us-goes-the-other-way |

Welcome to the China Patent Blog by Erick Robinson. Erick Robinson's China Patent Blog discusses China's patent system and China's surprisingly effective procedures for enforcing patents. China is leading the world in growth in many areas. Patents are among them. So come along with Erick Robinson while he provides a map to the complicated and mysterious world of patents and patent litigation in China.

AuthorErick Robinson is an experienced American trial lawyer and U.S. patent attorney formerly based in Beijing and now based in Texas. He is a Patent Litigation Partner and Co-Chair of the Intellectual Property Practice at Spencer Fane LLP, where he manages patent litigation, licensing, and prosecution in China and the US. Categories

All

Archives

February 2021

Disclaimer: The ideas and opinions at ChinaPatentBlog.com are my own as of the time of posting, have not been vetted with my firm or its clients, and do not necessarily represent the positions of the firm, its lawyers, or any of its clients. None of these posts is intended as legal advice and if you need a lawyer, you should hire one. Nothing in this blog creates an attorney-client relationship. If you make a comment on the post, the comment will become public and beyond your control to change or remove it. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed