|

I wanted to expand here on the article I recently published at CGTN. In that article, I pointed out that as of January 1, 2019, the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) enacted a national appellate court for civil and administrative IP cases. However, it is important to note that the new Intellectual Property Rights Court for Appeals (“IPRCA”) is not just an appellate court, as it can also serve as a trial court. In addition to hearing appeals in cases concerning invention patents, utility model patents, design patents, new plant varieties, layout design of integrated circuits, know-how, computer programs, and antitrust, the new IPRCA can also hear “major” and “complicated” first instance civil and administrative cases, as well as other cases that the SPC considers should be tried before the IPRCA. Exactly what the SPC considers “major” and “complicated” is not clear. Further, there is a catch-all category including “[o]ther cases that the SPC considers should be tried before the IP Court.” Until the new court has some cases under its belt and/or the SPC provides additional interpretations, on Dec. 28, 2018, the SPC issued the Provisions on Issues Concerning IP Tribunal (the “Provisions”) providing details regarding the IPRCA. See here for the Chinese version of the Provisions or here for a (quite imperfect) Google-translated English version. UPDATE: here is bilingual version.

Article 2 of the Provisions states that the IPRCA shall have jurisdiction over the following:

Other than jurisdictional issues, the Provisions also provide some additional details. For example, Article 4 provides for electronic service and disclosure (hallelujah!). Article 5 allows for electronic and online evidence exchanges, pre-trial meetings, and other court functions to maximize efficiency (again, wonderful!). Article 6 states that the IP Court may, if needed, travel to the location of the original trial or case. Article 8 states that case filing information may be inquired through the electronic litigation platform and the China Trial Process Information Open Network. Although this seems to anticipate a structure not in existence yet, it is certainly cause for excitement because one of the most limiting features of Chinese litigation is the lack of a full electronic case management system. I will continue to provide updates as we learn more about the new IP Court. For now, I am a huge fan and see this as a real game-changer. I look forward to finding out for what cases the new court will act as a trial court, and what resources will be available to ensure that the new organizational structure does not create a paralyzing bottleneck in an already-overloaded system. See my latest article on China’s new IP Appellate Court published by the China Global Television Network, the English-language news channel of the State-owned China Global Television Network group:

This will be a short post, as I just wanted to point out that the Supreme People’s Court very recently granted InterDigital’s petition for a retrial in a case involving royalties to be paid by Huawei. The high court’s ruling overturns a decision by the Guangdong Province High Court decision that certain InterDigital Chinese patents should not exceed 0.019 percent of the actual sales price of each Huawei product. I will try to get the raw data shortly, but the English-language report saying this is here: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/ip-law/interdigital-granted-huawei-patent-case-retrial-by-china-spc This is a big deal, as it will make it nearly impossible for Chinese and other companies to cite IDC v. Huawei for the purpose of supporting a 0.02% royalty rate. Indeed, Chinese damages law is quickly evolving to catch up with the rest of the progressive patent law and procedure we continue to see coming out of China. This is great news for innovation, for China, and for the innovators worldwide. Because not everyone can read Chinese, here are downloadable PDF copies of the bilingual versions of both orders from the Fuzhou court regarding the injunction against Apple requested by Qualcomm: Note that in China, each patent requires a different "case." Here, because there are two patents, there are two separate orders: one for Patent No. ZL201310491586.1 and one for ZL200480042119.X. I encourage you to read both orders, although they are largely the same.

Interesting facts from these documents:

Official Announcement: I have joined Dunlap, Bennett & Ludwig as Partner in Beijing and Houston!12/11/2018  I have officially joined the U.S. law firm of Dunlap, Bennett & Ludwig (DBL) as a Partner. DBL is a leading full-practice law firm with offices in 17 cities in the United States, China, Europe, Canada, and Puerto Rico. I will also be working with IntellStrategy, a Chinese patent agency. IntellStrategy is closely affiliated with, but separate from, DBL. The DBL-IntellStrategy alliance allows our team in North America, Europe, and China to achieve goals for our clients that other law firms, patent agencies, and consultancies cannot. For example, unlike many international firms which "cannot assist clients with Chinese IP law," IntellStrategy can directly represent Chinese and international clients in China's courts and before the Chinese patent office and Patent Reexamination Board. I will continue to split my time between Beijing and Houston. One of the biggest advantages is that I can represent clients in both the U.S. and China now! I am still technically a consultant in China because I am not Chinese and cannot be admitted to the Chinese bar (but thanks to IntellStrategy, my colleagues can!). However, I will continue to manage all types of IP issues in China, focusing on patent licensing and litigation. Further, I can use my Texas and New York bar cards again! I love my Chinese practice, but I miss arguing in court, taking deposition, and even (gulp!) managing discovery! Also, because DBL has an office in Europe, I can help companies enforce their patents simultaneously in the most important patent courts in the world. Joining me in my move will be my entire Chinese team, including patent litigation superstar, Dragon Wang. In case you are wondering, my short stint at my prior firm did not work out for reasons mostly related to conflicts. It is what it is, and I am very excited to work with my new colleagues!  The Fuzhou Intermediate People’s Court in China has granted Qualcomm's request for two preliminary injunctions against four Chinese subsidiaries of Apple Inc. The affected Apple products are the iPhone 6S, iPhone 6S Plus, iPhone 7, iPhone 7 Plus, iPhone 8, iPhone 8 Plus and iPhone X. The patents at issue enable users to adjust and reformat the size and appearance of photographs, and to manage applications using a touch screen when viewing, navigating and dismissing applications on their phones. I have not seen the order, but Apple is saying that the injunction only includes older versions of iOS. This is a developing issue and I will provide information as I receive it. What is clear, though, is that because this is a preliminary injunction, the injunction should NOT be stayed pending appeal. Also, there may be some political issues at play because whereas Qualcomm has paid its dues in China, Apple has never been a friend of China. One need only consider that Qualcomm is a supplier to some of the most important companies in China, whereas Apple is a competitor to those same companies. FYI: Here is a good article on some of the details as they are known to Reuters. Stay tuned - this one is big and could get bigger. I need to go now because I have to go file a bunch of cases in Fuzhou! IP House (China) Publishes Article on "Why Non-Practicing Entities (NPEs) Are Good For China"11/8/2018  A very interesting article was recently published in China on why NPEs are good for China. It focuses on iPEL, an NPE that has over 1000 Chinese patent families. The article was published by IP House, a Chinese publisher that has a contract with the Chinese government and courts to publish the most database of IP-related court decisions in China. For a PDF of the article in Chinese and English, click here. I have been asked for copies of various of my publications and presentations over the last few weeks, and have struggled with a way to make them available. Until I figure out a better way, here they are, with clickable links:

I. Overview The good news is that China’s entire civil litigation system has significantly improved, not just its patent enforcement system. Contracts are fairly and effectively enforced between foreign and Chinese parties. This means that if the contract is breached, a foreign company can get monetary damages and/or injunctive relief from a Chinese court so long as a foreign company: (1) executes a valid contract with a Chinese company, (2) that contract is sufficiently straightforward that a Chinese court can make a ruling of fact without significant investigation, and (3) the contract is not subject to China’s Technology Import Export Regulation (“TIER”), or the foreign company builds in a business advantage to incentivize the Chinese company not to escape the contract via TIER. This post addresses TIER and some ways to possibly deal with it, best practices for forming JVs with Chinese companies, and how to protect core and non-core IP in China. II. China’s Technology Import Export Regulation (TIER) A. TIER Restrictions Licensing is the primary means by which technology flows into markets and it may also set the stage for joint additional advances. The challenge to parties negotiating a licensing agreement is to find terms that are mutually beneficial, so that agreement is in the interest of both sides. Especially in the context of high technology, and associated intellectual property, it is critical that the parties have great flexibility in arriving at mutually beneficial terms as the market and circumstances demand. Unfortunately, TIER imposes rigidities as they relate to certain key terms, making it more difficult for the parties to reach agreement. The Chinese government, via the Ministry of Commerce (MofCOM) has mandated certain conditions be a part of any license of technology into China, regardless of whether those terms are in the parties’ contract, or even if these terms are specifically contradicted by contract. TIER mandates that foreign licensors fully indemnify Chinese licensees, surrender ownership to any improvements, and not prohibit marketing rights of Chinese licensees. The first potential problem with TIER pertains to indemnity terms, which govern which party should bear the burden if the licensee’s right to the licensed technology is challenged by a third party. Given the wide variety of circumstances, there is no single best approach to indemnity terms, which should be left to the parties to address in a mutually beneficial manner. TIER, however, inflexibly imposes all indemnity risks on the foreign licensor. Interestingly, many open source licenses are incompatible with TIER because they mandate that no indemnity is provided. For example, most open source licenses do not provide any warranties of non-infringement or any provisions for indemnification and some licenses specifically disclaim any warranty or indemnification. This obviously contradicts TIER and requires a violation of either the open source license or TIER. As use of open source-licensed code grows in China, this will be an important issue. Although TIER does not have a strong record of enforcement, open source licenses do. Indeed, the penalties for violation of such license terms can be draconian, including enjoining distribution and use of the software, as well as damages and attorneys fees. The second potential problem with TIER pertains to rights in technology improvements developed by the licensee. A licensor will often desire to have shared rights in improvements, in exchange for giving the licensee more favorable terms, such as by lowering any royalty payment. A licensor unable to share in improvements developed by the licensee risks being locked out by the new development, and so it may conclude that it cannot reach a deal with a Chinese partner due to the great uncertainty created by TIER. Absent the flexibility to negotiate shared access to improvements, a technology licensor may choose to avoid China completely, or to deal with an affiliated company that it can trust. Again, many open source licenses require any derivative works, including improvements, to be freely available to the public, so that the parties must violate either the open source license or TIER. The third concern pertains to licensing parties’ allocation of marketing rights. The business-driven bargaining in a licensing transaction often involves allocating market rights between a licensor and a licensee. For example, a given technology transaction may give a Chinese company the exclusive marketing rights in China and a U.S. company the exclusive marketing rights in North America. However, TIER prohibits licensing agreements that “unreasonably restrict[s] the export channels” of the licensee. Under this TIER provision the licensing parties cannot freely negotiate allocation of market rights according to their business needs and proposed level of license fees. Absent the flexibility to allocate marketing rights, a foreign licensor and a Chinese licensee may have to forgo their licensing partnership despite interest by both. B. Ways of Managing TIER Restrictions There are very few cases in China in which TIER has been asserted by China or Chinese companies to void specific provisions of a contract. Although this is good news, it is still not all that comforting to foreign businesses forced to accept uncertainty in licensing technology into China. There are a few ways of managing the potential dangers of TIER. First, it is clear that if a Chinese company voids important contract provisions using TIER, then that company will have significant problems ever working with a foreign company again. Foreign licensors, and foreign partners in general, will no longer trust such a Chinese entity to abide by its word. Such a consequence would be, therefore, bad for the Chinese entity as well as the foreign entity. Presumably, a Chinese company would only void the contract provisions via TIER in an instance where the value of doing so is very high – higher than the loss of future ability to work with foreign companies. Therefore, it may be possible to avoid such a case by providing business incentives (such as additional revenue, equity, or geographic share) to the Chinese partner in the event that the deal leads to great commercial success. A foreign company may also be able to protect itself by simply writing the TIER restrictions into the contract and valuing them properly. Alternatively, the licensor could simply accept the risk of TIER and go along with the contract as if TIER were not a factor. There are also other means of possible protection (in addition to the general “best practices” mentioned in the next section. For example, instead of licensing to a company in China, it may be possible to license to a Chinese company outside the PRC. The foreign entity could provide a written contract provision prohibiting import of the technology into China, but with the unwritten understanding that the licensor will not object to such import so long as the licensee does not attempt to exploit TIER to change the contract. While this is not exactly fair for the Chinese company, neither is TIER, and it shifts the uncertainty from the licensee to the licensor. While not a perfect solution, it does reallocate the trust issue to the Chinese side. Another option (at least for technology involving open source licensed technology) would be to contract to terms violating TIER, and then if anything goes wrong, seek to have the Free Software Foundation sue the Chinese company for violation of the open source license. This would be risky, and would require a very close relationship with the FSF and open source community. There are other possible creative solutions involving the foreign licensor using its own Chinese-owned subsidiary as the contracting party, or insisting that the licensee be a non-Chinese entity. The problem with all of these is that they have not been tested, because TIER itself has not been effectively tested. As with most business deals, it depends on the amount of risk that is tolerable to both sides. III. Best Practices on Joint Ventures/Technology Licensing with Chinese Companies While there is no guarantee that any contract will not be violated, there are many things that a foreign licensor can do to maximize its chances of making itself whole in the event that the contract is breached. Courts, judges, and arbitrators in China are getting more sophisticated each day. Also, such forums are generally quite fair and effective in enforcing foreign parties’ rights in China. However, the more complex the issue, the less clear the outcome and the slower the process. Therefore, several best practices should be followed in addition to general best practices regarding technology licensing outside of China. A. Make the contract simple: define breach and liquidated damages Although courts in China are more sophisticated than ever, they are burdened with a huge number of cases. They also are more reticent to give injunctive relief of large damages if they are not sure they are correct in their judgment. Therefore, make it easy for them: make the contract simple. Define specifically what constitutes a breach and what the penalty should be. Liquidated damages are a must. Make it so that all the aggrieved party has to show is: (1) there is a contract, (2) the contract was breached, and (3) the parties agreed at the outset what the penalty for such a breach would be. This should lead to a very fast and effective judgment. B. Define “Confidential Information” (“CI”) clearly and put the onus on the licensee to show that information is not Confidential Information Courts in the US get bogged down in determining what is CI under contracts. Chinese courts have the same problem. A solution to keeping up with what falls under CI is to make every bit of information provided to the Chinese partner fall under the definition. The contract should provide that all information is assumed to be CI, unless the Chinese party objects in writing within a specific period, say two weeks from receipt. There should be a provision for determining disputes quickly, including destruction of any material or information provided to the licensor that cannot be agreed as to confidential nature. Then, the licensor should provide a regular report to the licensee listing the information that it has sent the licensor and that it has received from the licensee as not constituting CI. Such a process would allow a judge of any dispute to quickly determine what was CI and provide quick redress. C. Choices of venue and law and right to enforce judgment in China Although the courts and arbitrators in China can now generally be trusted, if the licensee is particularly well connected, it may make sense to dictate that the choices of law and venue be in the licensor’s jurisdiction with the right to enforce any resulting judgment or adjudication in China. D. Get a full list of officers, executives, and principals The licensor should obtain a notarized list of officers, executives, and principals, with photos. The guards against the possibility that licensor’s CI and IP could end up in another company headed or run by the principals of the licensee. Depending on the size of the licensee and its reputation, it is very possible for the licensee to close down, move, and start up again under a new company name. Proving that this has happened will be much easier if the licensor has a list of those holding power at the original licensee. It is probably also worthwhile to get a list of lead engineers on the project. E. Have in-document translations of each section The contract may be in either English or Chinese, whichever the parties prefer. It is important to have in-document translations of each section. This allows for easier negotiation and for easier adjudication. One language should be controlling (likely the language corresponding to choice of venue). It may be helpful to get a notarized official translation of each section. This is not required, but for large deals is likely worth it. F. Lay a trap Foreign licensors of software may want to lay a trap by including in comments to the code or elsewhere specific information linking the code to the licensor. For example, add the abbreviation for the company as a note hidden multiple times throughout the code. This way, in case the licensee ever tries to argue that the code is theirs, they will have a hard time explaining why links to the licensor are there. IV. Top IP issues when forming a joint venture in China A. Keep control One key to protecting IP in any deal with a Chinese partner is to make sure that the foreign entity will control the JV. Since most foreign investors wish to maintain control over their Chinese JV entity, this issue is usually paramount. Most foreign investors strive to obtain at least 51% ownership interest in the equity JV, assuming this gives them the right to control the company. However, control over a Chinese JV actually comes from the following: · The power to appoint and remove the JV’s Legal Representative. · The power to appoint and remove the General Manager of the JV company. The JV agreement must make clear that the General Manager is an employee of the JV company employed at the full discretion of the Legal Representative. Note that this agreement will be enforced under Chinese law and its controlling version should therefore be in Chinese. · Control over the company seal, or “chop.” The JV partner that controls the JV’s registered company seal has the power to make binding contracts on behalf of the JV company and to deal with the JV company’s banks and other key service providers. B. Safeguard intellectual property the traditional way Multinational companies still struggle to protect their intellectual property in China, and JVs are particularly vulnerable. Companies have traditionally had some success with more pragmatic, operational efforts, including the following:

C. Improved and New Intellectual Property In the growth and development of a JV, new IP will come about, and these will be regarded as belonging to the JV. Therefore, it is also up to the JV to assign it or to apply for protection. If the foreign investor only holds a minority stake in the JV, then s/he may find themselves in a weak position regarding control over new IPRs. It is recommended to deal with these matters in the JV agreement before they become problems. *Note the prior discussion of TIER in this regard. D. License/Royalty Fees Licensing or royalty fees from the transfer of IP in a JV deserves close attention. In China, royalties are subject to income withholding tax and business tax. Also, in some sectors, the royalty rate may have a ceiling, such as a 0.3% royalty rate ceiling of sales revenue in the retail sector for the use of a trademark. E. Getting the money out of China and paying taxes Transferring money out of China has always been a challenge and is only getting harder. See, e.g., https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/29/business/economy/china-tightens-controls-on-overseas-use-of-its-currency.html. Make sure to have a plan to transfer any revenue out of China, or keep it there, and know what taxes will be applied.  Does anyone want to meet in Chicago Saturday through Tuesday? I will be there for the IPO Annual Meeting. It would be great to connect! Email me at erick@chinapatent.law!  This past week, we found out that the Intermediate People’s Court in Fujian, China issued a preliminary injunction against Micron in favor of Taiwan-based UMC and Fujian-based Jinhua. See the great article by IAM here. The injunction covers “certain Crucial and Ballistix-branded DRAM modules and solid state drives. The surprising aspect was not necessarily that an injunction was issued (this happens in over 95% of Chinese patent wins) but that this was a PRELIMINARY injunction ("PI"). Like most jurisdictions, including the US, it is difficult in China to obtain a PI. The main reason is proving infringement and that the patent holder will be irreparably harmed. Specifically, Chinese courts generally consider the following factors in determining whether to issue PIs in patent cases:

Many sources seem to assume that there was some political forces at play in the Fujian court's decision. I do not dispute that surely the plaintiffs here had the hometown advantage. However, I believe the power of this advantage is not as significant as others may assume. There is a reason that in the Eastern District of Texas was popular as a venue. Similarly, there is a reason that large companies like Google have contributed a fortune in lobbying the US government to ensure they can be sued only in Northern California or Delaware. In any case, a leading US semiconductor has been -- at least temporarily -- enjoined from making, using, selling, importing, or exporting its products. So if there are political forces are play, what are they? Well, I predicted them here: ... and here: To reiterate, China is very likely to use its patent enforcement system to catch up in areas of technology it feels are important. China sees its huge foreign dependence for semiconductors as a national security issue. This is entirely reasonable given that semiconductors are the brains behind every device we use these days, including surveillance, computing, and artificial intelligence.

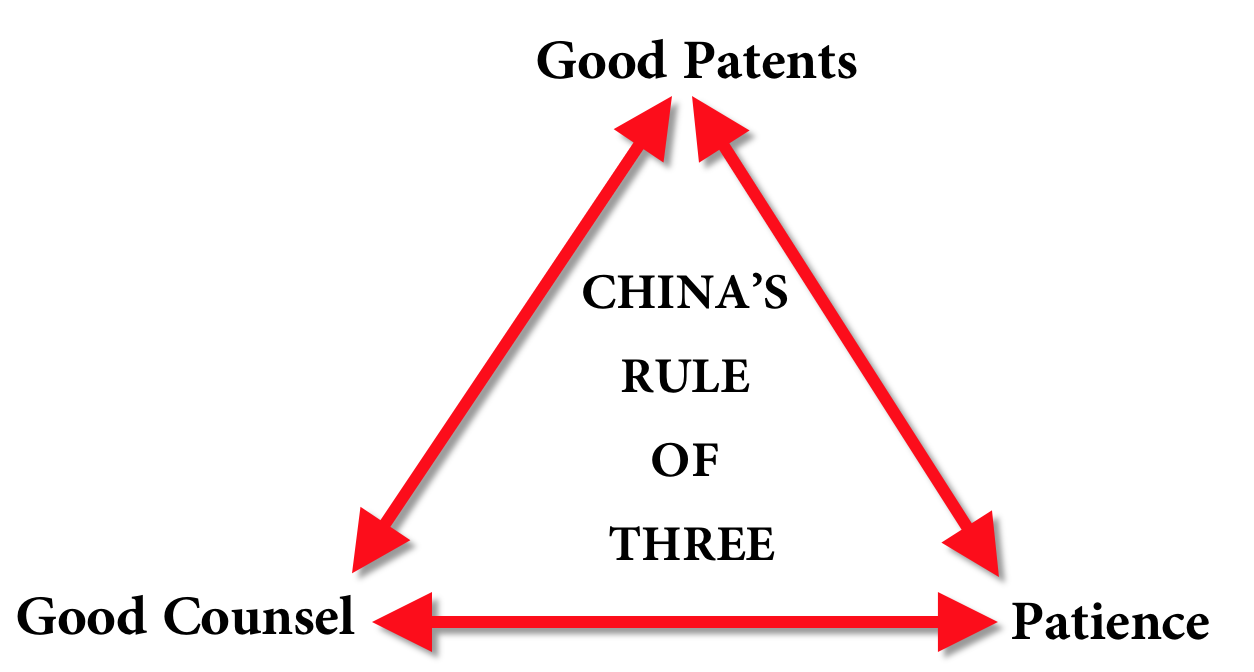

The Chinese patent litigation play could several ways. For one, NPEs attacking foreign competitors to Chinese companies will help. A more "Jedi mind trick" play, though, is to for Chinese companies to simply attack their foreign competitors in patent litigation. When the Chinese company wins the case and gets their injunction, that's when the magic comes in. With their boot on the neck of their foreign competitor, they can name their price for settlement. This price could come in terms of money, but it could mean sharing sensitive technologies -- technologies that China cannot buy due to the US increased protectionism and the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). Because settlements are generally confidential and not reported, such forced technology transfer may fly under the US radar. No matter how important the "home field advantage" was in the latest Micron case, it likely played some role. Fortunately for Micron, the patents covered only a portion of its products. But this is not the end -- far from it. At some point, the US may find that it would have been easier to simply approved the purchase of Micron by Tsinghua Unigroup.  The China Patent Blog is honored to be ranked as a top Business Law website and a top Intellectual Property website by FeedSpot! I greatly appreciate everyone who reads and follows the blog and commit to continuing to provide interesting and useful insight into the world of Chinese patent law and litigation. Blog on!  I have said many times that China is now the best place in the world to enforce patents. While the Chinese system is very good and getting better every day, there are some limitations. All three of these should be obvious, but in recent conversations with folks at IPBC Global in San Francisco, I realized that it may be worth pointing these out. Specifically, in China, you will win if you have all three of these. Also, you will still likely win if you have two out of these three (and that ain't bad). But if you have only one or none of these, even China cannot save you. 1. First, you should have good patents. Note I did not say perfect, or even near-perfect patents. As long as you can make a reasonable argument to a judge regarding infringement and validity (which are adjudicated separately in China), you should be fine. I could go on for hours about a quality patent is, but suffice it to say the bar is far lower in China than it is in the US or Europe.

2. Second, you should have good counsel. For foreign companies, executives, and in-house counsel, this can be difficult. Language barriers are compounded by cultural obstacles and unfamiliarity with Chinese law and procedure. One way to deal with such challenges is to hire foreign counsel (eg, US companies hire their typical US litigation counsel) to manage local Chinese counsel. However, in addition to increased costs and inefficiencies, such an approach can lead to mistrust among the legal team. Further, the foreign legal team is usually no better equipped to deal with either the language and cultural differences or the lack of understanding of the Chinese legal system. Because of these problems, more and more companies are bypassing foreign firms and hiring Chinese law firms directly. Although this solves the lack of coherency and trust among the legal team, there is still a cultural, linguistic and legal understanding gap. Plus, without the help of an international law firm, choosing a Chinese law firm can be confusing due to lack of data and connections. For patent litigation, there are still only around ten firms I would trust. These are good firms technically and legally, but the passionate "win at all costs" attitude of top US lawyers is generally not there. Further, the levels of service even at top Chinese are lower than at foreign firms. Do not expect an answer overnight, and do not expect anyone to work on a holiday. There are exceptions, as some firms (including mine) are hiring experienced foreign patent litigators for their strategy prowess as well as for case and client management. Nonetheless, no Chinese firm is up to the quality of my former firms Weil Gotshal or McKool Smith or other top foreign law firms. They will get there, but it will take a few years. One trap for the unwary involves how most Chinese law firms are organized and how their attorneys are compensated. First, it is important to understand that the titles of ‘partner’, ‘senior partner’ and similar designations can mean little to nothing. It is very easy to hire an attorney into a Chinese law firm as a so-called ‘partner’, because most partners draw no salary. Indeed, many firms in China have doubled in size overnight simply by adding names at no additional expense. Therefore, many partners are not experienced lawyers and do not have high-quality experience. This dovetails with the other issue: how most Chinese firms compensate their lawyers. Most Chinese law firms pay their partners on an extreme eat-what-you-kill system. Partners receive no salary, but keep between 70% and 85% of the business they bring in. This is great for lawyers with a lot of business, as it enables them to get rich fast. However, if a partner needs help from associates or staff, he or she must pay them out of his or her own pocket. This structure creates an incentive for partners in Chinese firms to:

This is especially true for contingency fee cases, because the partner must pay for any extra work himself or herself upfront, but will not receive revenue until much later, if at all. The result is that many companies which believe that they are hiring a firm with a plethora of lawyers are hiring only a single partner who refuses to work with other lawyers or staff. I have been involved in cases when I was in-house where the Chinese attorney was significantly overburdened, but refused to seek help because of what this would cost. Obviously, this can be a serious problem and adversely affect a case. Clients should obtain a written explanation of how their Chinese counsel are compensated. If this is not forthcoming, they should seek other counsel. If the firm uses an extreme eat-what-you-kill model, then the client should contract not with it, but with the specific attorneys it wishes to work with, including associates. The client can also contract with attorneys from multiple firms – although this may lead to inefficiencies and unwillingness to work together. Alternatively, the client can simply refuse to hire any firm with such a system. Some Chinese firms have adopted a more team-oriented approach, but they are hard to find. 3. Third, if you want to win (or just stay sane) you should have plenty of patience, especially before filing. Like US law on declaratory judgments (DJs), Chinese law allows a party that has been threatened with an infringement action to file a pre-emptive lawsuit to prove non-infringement. This procedure is rarely used in China, largely because of the prerequisite actions that are generally required before filing such a declaratory judgment action. No specific act or regulation has set clear rules for non-infringement declarations. However, the Supreme People’s Court has issued guidelines and judicial interpretations on this subject. These provide that the following conditions should generally be met before bringing proceedings to obtain a declaration:

Unlike under US law, this effectively gives a patentee time to file a litigation after sending a warning letter. This area of law is likely to evolve over the next few years; but for now, a declaratory judgment action is difficult to use by an accused infringer without a tactical mistake by the patent owner. Importantly, this provides no disincentive for the patent owner to contact and negotiate with the accused infringer before filing a lawsuit. Given this lack of meaningful DJ jurisdiction, it is no wonder that Chinese judges expect that the patent owner has not just contacted the defendant before filing, but also reached a reasonable impasse in negotiations. For non-standard essential patent (non-SEP) cases, that impasse can happen very quickly. For example, if the alleged infringer simply does not respond after a few contacts, then the patentee has no choice but to file. Such a non-responsive party can also be quickly sued in a SEP case since there is no other option. If the accused infringer does respond and enter negotiations, then SEP and non-SEP cases differ. In non-SEP cases, if the patentee subjectively believes that the negotiations are not going anywhere, or the would-be defendant is lowballing them, then this is a sufficient impasse to file that patent litigation. However, for SEP cases, the bar is higher. China has seen two SEP plaintiffs seek an injunction, and both patent owners were granted the injunction. My colleague, Austin Chang, has previously summarized the IWNCOMM v. Sony case on this blog. See also this excellent IAM article for additional information on the IWMCOMM case. The second adjudicated SEP injunction case found Huawei being granted an injunction against Samsung. IAM also published another great article in which Allen & Overy Shanghai partner David Shen analyzed why the injunction was issued. Although there are many issues involved in both the IWNCOMM and Huawei cases (including that both companies are Chinese, as are over 90% of patent plaintiffs in China), the take-home message is simple. The party most at fault for the impasse in negotiations will likely lose the SEP injunction battle. Put another way, the more reasonable party will prevail. In IWNCOMM, although IWNCOMM did not provide claim charts to Sony, the court found that the patentee has no duty to provide claim charts if the intended licensee possesses sufficient documents to determine the likelihood of infringement. In this case, Sony had been uncooperatively asking IWNCOMM to provide claim charts since the parties began its negotiation in 2009 all the way through 2015 at the same time that Sony had, in its possession, sufficient documents to make a determination regarding infringement of the disputed patent. The court determined that such intentional delay warranted IWNCOMM’s request for an injunction. In the Huawei case, the court found that Samsung employed delay tactics in the cross-license negotiation and took improper positions. Further, the court held that the license rate proposed by Huawei met the FRAND obligation since the offers were not excessively far above the global aggregate rate range (which was redacted by the court). Again, the message was to be reasonable and honest with the court. Based on Huawei and IWNCOMM, it is clear that if an SEP owner wants an injunction in China, they must be patient and reasonable. These is no specific timetable for this. Many defendants will try to string the patent owner along for years. This is clearly unacceptable. But the defendant must have an objectively reasonable opportunity to analyze the patents involved and whether the offer by the patentee qualifies as FRAND. Note the word OBJECTIVELY. Although time will tell, common sense dictates that a party should need no more than a few months in this regard. That is, if the patent owner provides to the accused infringer claim charts and/or information about other licenses previously granted and also offers to have its technical staff discuss the patents, their reads, and the license offer, then a delay more than a 2-4 months is likely unreasonable on the part of the accused infringer. Other factors can also impact this equation, including the attitude of the defendant during discussions, how long it takes to schedule calls/meetings, and the life of the patents. However, like I said earlier, if a defendant simply will not respond or communicate with the SEP owner, then clearly an impasse has been reached and a lawsuit may be justifiably filed. For SEP cases, patience is a required part of the triangle. For non-SEP cases, it is just advisable. In conclusion, the rule of three is a triangle in which the strength or weakness of each corner can be offset by the others. The ideal case is one with perfect patents, top counsel, and a very patient client, but perfection is not required (or expected). To be safe, make sure you have two out of the three, or even better, a decent portion of all three.

I have had a number of requests for my slides from my presentation at LES in Chicago, so I thought I would make them available to everyone here:

|

Welcome to the China Patent Blog by Erick Robinson. Erick Robinson's China Patent Blog discusses China's patent system and China's surprisingly effective procedures for enforcing patents. China is leading the world in growth in many areas. Patents are among them. So come along with Erick Robinson while he provides a map to the complicated and mysterious world of patents and patent litigation in China.

AuthorErick Robinson is an experienced American trial lawyer and U.S. patent attorney formerly based in Beijing and now based in Texas. He is a Patent Litigation Partner and Co-Chair of the Intellectual Property Practice at Spencer Fane LLP, where he manages patent litigation, licensing, and prosecution in China and the US. Categories

All

Archives

February 2021

Disclaimer: The ideas and opinions at ChinaPatentBlog.com are my own as of the time of posting, have not been vetted with my firm or its clients, and do not necessarily represent the positions of the firm, its lawyers, or any of its clients. None of these posts is intended as legal advice and if you need a lawyer, you should hire one. Nothing in this blog creates an attorney-client relationship. If you make a comment on the post, the comment will become public and beyond your control to change or remove it. |

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed