In late 2020 and early 2021, approximately 20 patent infringement lawsuits and administrative actions were filed in China against Netgear and Arlo. The Chinese plaintiffs seek damages and injunctions against the manufacture and export of several of the companies’ most popular products, including routers, switches, doorbells, and home security products. These lawsuits were filed by at least six different Chinese companies across several Chinese jurisdictions, including IP Courts, Intermediate Courts, and administrative agencies. Netgear disclosed a small number of the lawsuits in its quarterly report in October 2020, but its upcoming quarterly report will likely include the additional cases. At least four Plaintiffs in those lawsuits appear to be operating companies in China, at least one of which seems to be a State-Owned Enterprise (i.e., owned at least partially by the Chinese government). One of the companies, Beijing Tianxing Ebel Information Consulting Co., Ltd., appears to be affiliated with “Beijing Star,” a subsidiary of Reignwood Group, a Chinese conglomerate with diverse business interests as Red Bull energy drinks, helicopter fleets, and worldwide resorts. The reason that multiple Chinese companies are attacking Silicon Valley networking powerhouses is unclear. Whether it is political or just smart strategy (both companies appear to do a significant portion of their manufacturing in China, putting their supply chains at risk), it may be an indication of things to come. To the extent that there is coordination between the companies, this would be a first for patent litigation by Chinese companies against foreign companies in China. The six Chinese companies and the 17 case numbers are below. Chinese Plaintiffs: Dunjun Technology Co., Ltd. Gao Ping Yao Yi Trade & Commerce Co., Ltd., Shenzhen YuanYu Investment Co., Ltd., Shandong Chengzi Medical TechnologyCo., Ltd., Yunwen Impression Advertisement Co., Ltd Beijing Tianxing Ebel Information Consulting Co., Ltd. Case Numbers: Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初878号 Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初877号 Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初1038号 Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初936号 Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初934号 Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初960号 Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初961号 Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初1231号 Beijing IP Court-(2020)京73民初1232号 Beijing IP Court-(2021)京73民初179号 Jinan Intermediary Court- (2021) 鲁01民初76号 Jinan Intermediary Court- (2021) 鲁01民初87号 Jinan Intermediary Court- (2021) 鲁01民初183号 Jinan Intermediary Court- (2021) 鲁01民初185号 Jinan Intermediary Court- (2021) 鲁01民初839号 Jinan Intermediary Court- (2021) 鲁01民初840号 Shanghai IP Court- (2020) 沪64民初691 We all know about Marshall and the EDTX as well as Waco and the WDTX, but don't forget about Houston and the SDTX! My partner, Miranda Jones explains here. Follow Porter Hedges's New Patent Litigation Law Blog here: https://www.porterhedges.com/patent-litigation-law-blog

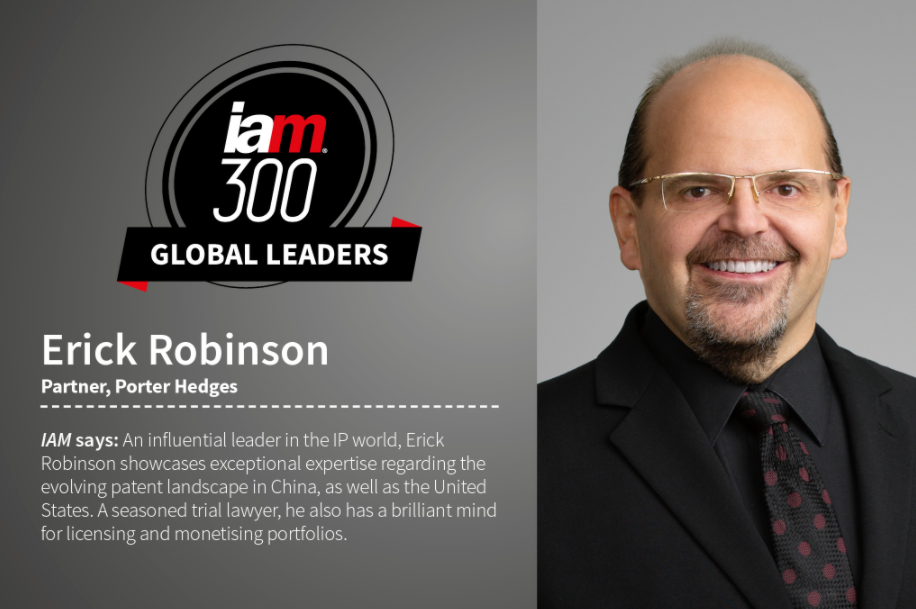

#PatentsAreBack #PorterHedges #patentlitigation #patents #texaspatents #SDTX #HoustonPatents I am humbled to have been identified as an Intellectual Property Global Leader by IAM: I particularly appreciate this honor as both my Texas and Chinese patent litigation practices continue to grow exponentially at my new firm. I am looking forward to achieving great things for my amazing clients at Porter Hedges LLP.

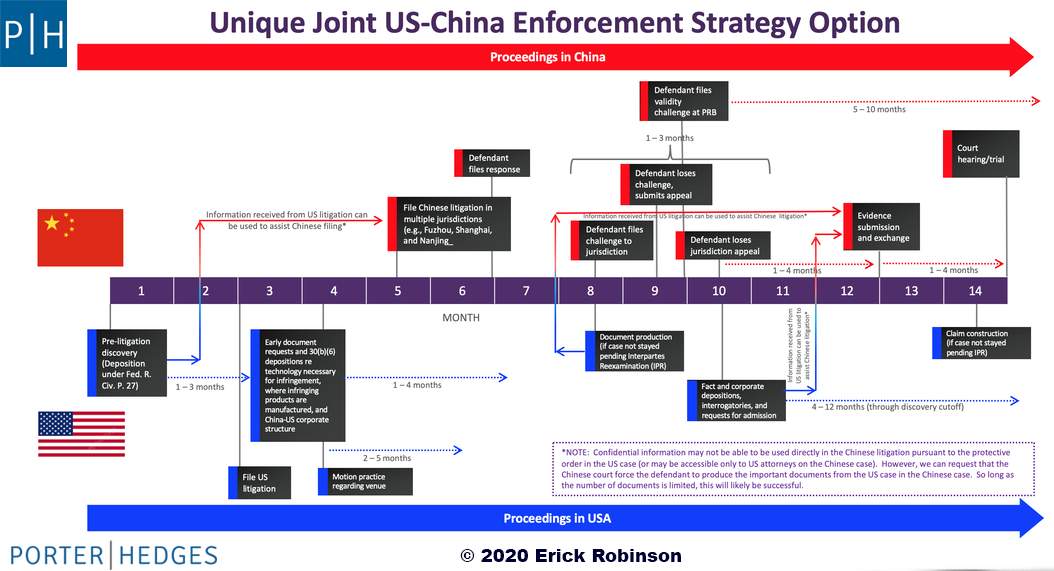

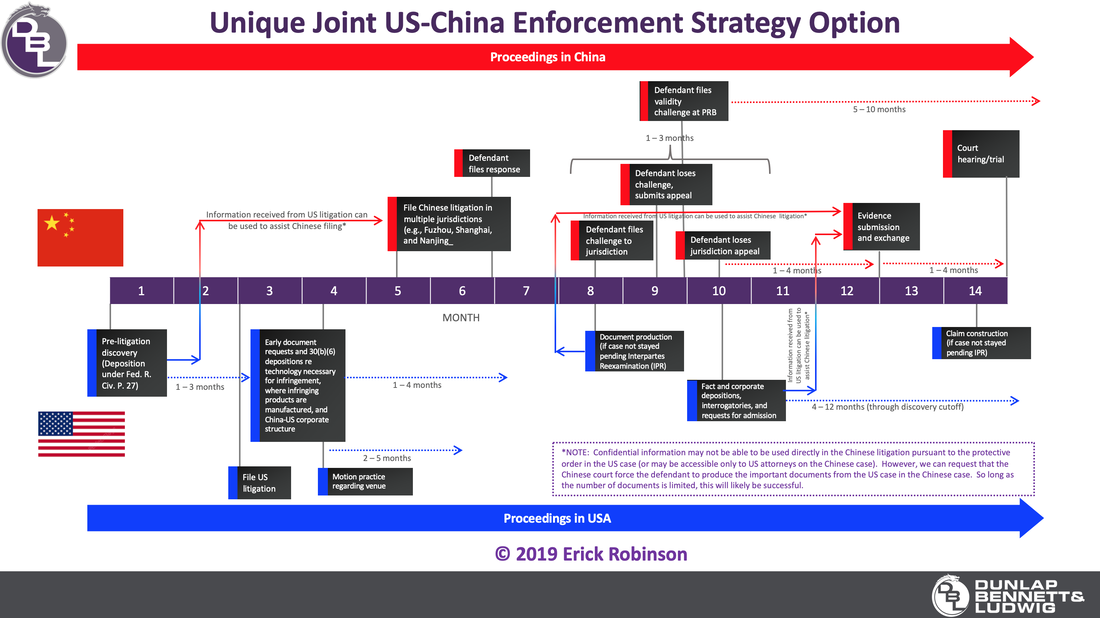

Thank you to my clients, colleagues, and to IAM! #PatentsAreBack #PatentLitigation #ChinesePatents #TexasPatents I have kept my head down for a while, but wanted to let everyone know why: I have joined the Houston office of Texas litigation powerhouse Porter Hedges LLP as a partner in the patent litigation group. We have a brilliant and experienced team of 120 attorneys ready to zealously represent our clients. Porter Hedges has one of the largest litigation practices in Texas by both headcount and revenue. This means that we have the experience and firepower to take on anyone in the patent litigation universe in either the US or China. I now have the support at both the partner level as well as top associates (we pay BigLaw salaries to our associates) to enforce patents against the biggest and most well-heeled infringers. I have been very lucky to have helped create one of the top plaintiff-side patent litigation practices in both the US and China. I have a great team in China headed in Beijing by my good friend and colleague, Dragon Wang, and together we will continue to enforce patents across Mainland China. My US practice over the last two years has gone from "I'm sorry, I am a US litigator but do not practice there" to a go-to patent litigation practice, especially in the Western District of Texas (see my other blog, the WacoPatentBlog.com). Apparently litigating in the US for 15 years before my time in-house and in China was still useful. Now, I am litigating in the US, China, and both. In fact, we have been quite successful at leveraging the speed of a Chinese case (along with the 99% chance of an injunction) with a parallel US litigation in Texas, Delaware, or the ITC. On the flip side, one of the few drawbacks of Chinese litigation is the lack of substantive discovery, so we can often use US discovery to make the Chinese case even easier (yes, there are potential protective order issues in the US, but often we can just get the judge in China to order production of a subset of the US production). Here is on overview of how it works: I am looking forward in the coming days, months, and years to continue to build the best plaintiff-side patent litigation practice in the country. If you or your company would like to chat, please email me at [email protected] and let's get it going!

I am honored to be selected for the IAM Strategy 300 for the sixth straight year. I greatly appreciate IAM, as well as my clients, colleagues, and friends for their trust ! I especially thank to my US and China teams for helping me create a one-of-a-kind patent litigation practice. When I left my very good in-house position at Qualcomm a little over five years ago with no clients, things could have gone horribly wrong. There have been hiccups, of course, but I during this period, I have been honored to work with the top patent litigators in the world. What started as a limited IP practice focused only in China has become a worldwide patent litigation and licensing practice focusing on the US, China, and Germany. With the growth of litigation funding for US patent litigation and fair judges like those in the Western and Eastern Districts of Texas, the US part of my practice has continued to flourish. The magic, though, is combining US, Chinese, and German patent law into a worldwide enforcement campaign. Successful patent enforcement is no longer limited to one or even two countries. Rather, it is a vital part of business planning, and can require access to unfamiliar jurisdictions. As the world gets smaller and smaller, I have been honored to help clients successfully litigate in the US, Mainland China, Taiwan, Germany, France, Brazil, Vietnam, Singapore, and Italy. I love what I do, and although that is generally enough, I appreciate the occasional accolade from great folks like IAM to substantiate that I am making a difference. I owe all of my partners, associates, assistants, friends, and clients for supporting me over the years, and especially during this horrid 2020. Here's to a better year next year, and to great patents and technology! 多谢! See my article on the "Albright Doctrine" and how the PTAB just adopted it: https://www.wacopatentblog.com/waco-patent-blog/the-strengthening-of-the-albright-doctrine-re-iprs-at-the-ptab #WacoPatents #Albright #JudgeAlbright #WDTX #DBLpatents #DBLlawyers

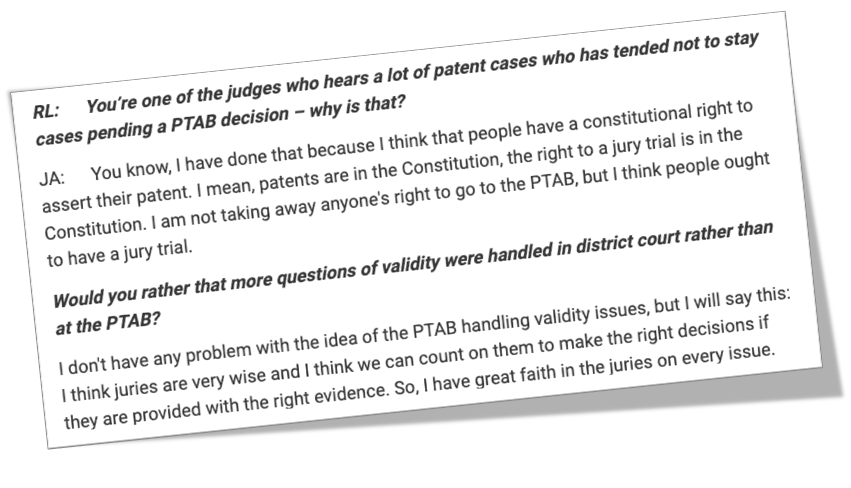

IAM included my client’s settlement with Xiaomi as one of the top ten IP stories of 2019!12/30/2019  Today IAM Magazine listed my client’s recent settlement with Xiaomi as one of the top ten IP events of 2019! The settlement involved high seven figures (in USD). My firm and I filed six patent lawsuits in the Nanjing Intermediate Court for Advanced Codec Technologies’ (“ACT”) against Xiaomi in early 2019. At issue were six standard-essential video compression patents. Why Is This Case Important? 1. As IAM points out, this is important because ACT is a Non-Practicing Entity (“NPE”). Given recent “the sky is falling” nonsense from the Big Infringement lobby, this is a big deal (but is fully indicative of the litigation market for NPEs and operating companies in China right now). 2. The patent owner is an American company litigating against a powerful Chinese company during the middle of the trade war between the US and China. 3. The patents were standard-essential patents, which typically are more complex to litigate and require more time both pre- and post-filing in China (as well as worldwide). 4. All six patents are nearing their expiration date, which means that there was no threat of an injunction — this was about money damages only. 5. This is one of the largest patent litigation settlements in the history of China, and certainly the highest for an NPE. This result says great things about the Chinese patent enforcement system, which over the past few years has emerged as a top patent litigation forum. Also working with me on the case from Dunlap, Bennett & Ludwig were partner Dragon Wang, senior associates Bing Wu and Tianqi Yu, and associates Yannan Li and Ada Liu. If anyone has any questions or would like to discuss the case, please email me at [email protected]. Tonight I was in Washington, DC to be interviewed by CNBC World. I am still getting over jet lag from my return from Beijing, but I think I was fully awake throughout the interview. Please email me and let me know what you think!  Photograph by Waco Tribune-Herald Photograph by Waco Tribune-Herald My WacoPatentBlog co-author, Daniel G. Henry, recently sat down with Judge Albright for a Q&A. Here is some of that conversation: https://www.wacopatentblog.com/waco-patent-blog/q-a-with-judge-alan-d-albright  My friend, Mark Cohen, recently posted an article entitled "Where have all the cases gone… long time passing…" While I greatly respect Mark and value his insight into China, this particular post is disappointing. Mark, especially since he moved to academia, has pushed for thorough transparency, which is a good thing. Specifically, he emphasizes that patent litigation statistics should be taken with a grain of salt. Again, this is good advice, because there is no PACER, Lex Machina, much less a Lexis-Nexis or Westlaw to search or analyze cases. Patent cases from the Beijing IP Court can be obtained via IP House, which Mark used in one of his analyses here. But in this post, Mark makes an alarming accusation based only on the statement "ha[d] heard from various [unnamed] sources." That accusation is that the Chinese government (or its courts, sua sponte ) are slowing down and not accepting patent and trademark cases for political reasons. I will not opine on trademark cases as I do not file enough of these personally to support or challenge this allegation. But as for patent cases, including those filed by US NPEs, this is not my experience. Stating that "cases can be decided but only upon approval from the Supreme People’s Court" is obviously alarming, but without proof, this seems to be just more US politicizing of the trade war. Mark Cohen is a smart guy who normally demands not just evidence, but thorough evidence. Mark and I have reasonably disagreed in the past on the amount of data needed to show just how well China's patent litigation system has evolved over the last five years or so. We did not and still do not see eye to eye, but I always appreciated his dedication to sufficient public data. Here, I just want to point out that this is an opinion based solely on hearsay statements of unidentified sources. Further, as someone in the middle of many patent cases between foreign (including US) entities, I have not seen any political maneuvering. I have not experienced any slowdown or effect in the courts in which we file. Beijing has come to a standstill, but that is because of the number of backed up cases, not political action by the Chinese government or courts. In fact, we have had great successes and moved even SEP cases more quickly than I had thought we would. Like Mark, I invite anyone who is willing to go on the record to provide such experiences to share their information. Until then, I worry that the United States is listening to people like Marco Rubio more than their own common sense and actual experiences. I will not apologize for doubting folks like Senator Rubio and other US bureaucrats and politicians who get paid to demonize China. Please email me any examples of the Chinese courts or government unfairly slowing or rejecting patent (or trademark) cases.  My new blog is now online! David G. Henry and I have created the Waco Patent Blog to provide news and information regarding patent litigation the exciting Western District of Texas, Waco Division! Join us as we explore this exciting patent venue! Don't worry, though: I will still be managing this China Patent Blog as I split my time between China and Texas! https://www.wacopatentblog.com/waco-patent-blog/may-19th-2019 #dbllawyers #albright #wdtx #patentlitigation #waco #wacopatents #patents  My firm, Dunlap Bennett & Ludwig won a significant victory in a high-profile patent lawsuit. A Texas U.S. District Judge doubled a jury award to $24.5 million and added $4.75 million in attorneys’ fees and expenses for a toy company that won a case against Telebrands Corporation. In doing so, the judge found that Telebrands infringed two patents on a water balloon device. The judge also found that Telebrands’ intentionally copied the patented product and used obstructionist tactics throughout the case. The product “Bunch O Balloons” is produced by toy manufacturer ZURU pursuant to a license with Tinnus. Telebrands copied the product and released an “As Seen on TV” infomercial-style ad campaign calling its product “Balloon Bonanza." In 2015, Tinnus and ZURU sued Telebrands, claiming that Telebrands’ product infringed their patent. Judge Robert W. Schroeder III issued a 64-page opinion in which he added to the plaintiffs’ trial victory by doubling the jury award to $24.5 million. He also awarded plaintiffs $4.75 million in attorney fees and expenses and denied Telebrands’ motions for a new trial. The opinion is available here. For more information, see the DBL website summary or the IP Law360 story.  UPDATE: For those having problems accessing the podcast, it is available directly from this blog at this link. My firm recently launched a new podcast, Blackletter Podcast. On the most recent podcast, Tom Dunlap interviewed my partner, Dragon Wang, and me regarding protecting and defending intellectual property in China. Here is a link to the podcast on iTunes: Tom Dunlap speaks with Erick Robinson and Dragon Wang, attorneys for Dunlap Bennett & Ludwig, about how to protect and defend intellectual property in China.  On 4 January 2019, the National People’s Congress published a draft amendment to the Patent Law (the “Amendment”). See the Chinese version here. The Amendment is open for public comments through February 3, 2019 via the NPC website. China Law & Practice (ALM) published my article analyzing the provisions of the Amendment here. Unfortunately, it is behind a paywall. However, here is a redline of the changes in English. Email me if you have any questions or if I or my firm, Dunlap, Bennett & Ludwig can assist you regarding Chinese IP! |

Welcome to the China Patent Blog by Erick Robinson. Erick Robinson's China Patent Blog discusses China's patent system and China's surprisingly effective procedures for enforcing patents. China is leading the world in growth in many areas. Patents are among them. So come along with Erick Robinson while he provides a map to the complicated and mysterious world of patents and patent litigation in China.

AuthorErick Robinson is an experienced American trial lawyer and U.S. patent attorney formerly based in Beijing and now based in Texas. He is a Patent Litigation Partner and Co-Chair of the Intellectual Property Practice at Spencer Fane LLP, where he manages patent litigation, licensing, and prosecution in China and the US. Categories

All

Archives

February 2021

Disclaimer: The ideas and opinions at ChinaPatentBlog.com are my own as of the time of posting, have not been vetted with my firm or its clients, and do not necessarily represent the positions of the firm, its lawyers, or any of its clients. None of these posts is intended as legal advice and if you need a lawyer, you should hire one. Nothing in this blog creates an attorney-client relationship. If you make a comment on the post, the comment will become public and beyond your control to change or remove it. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed