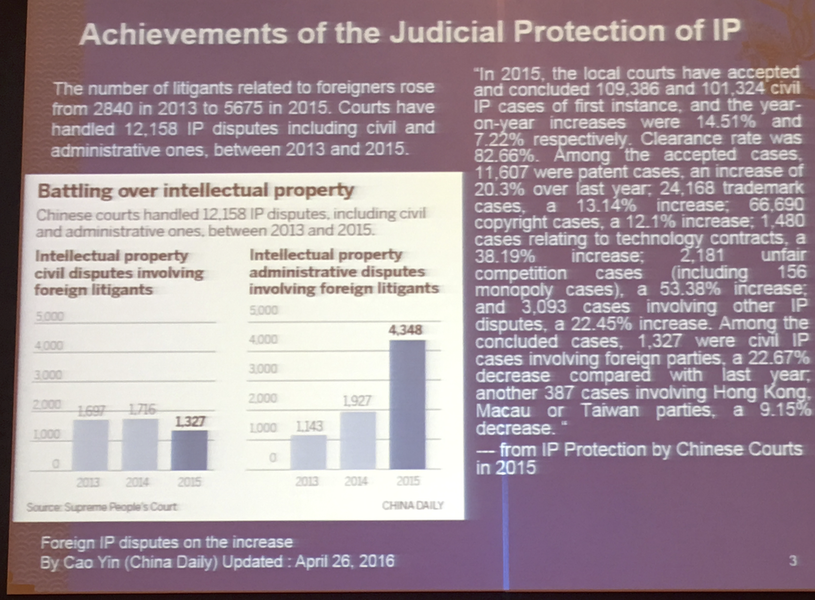

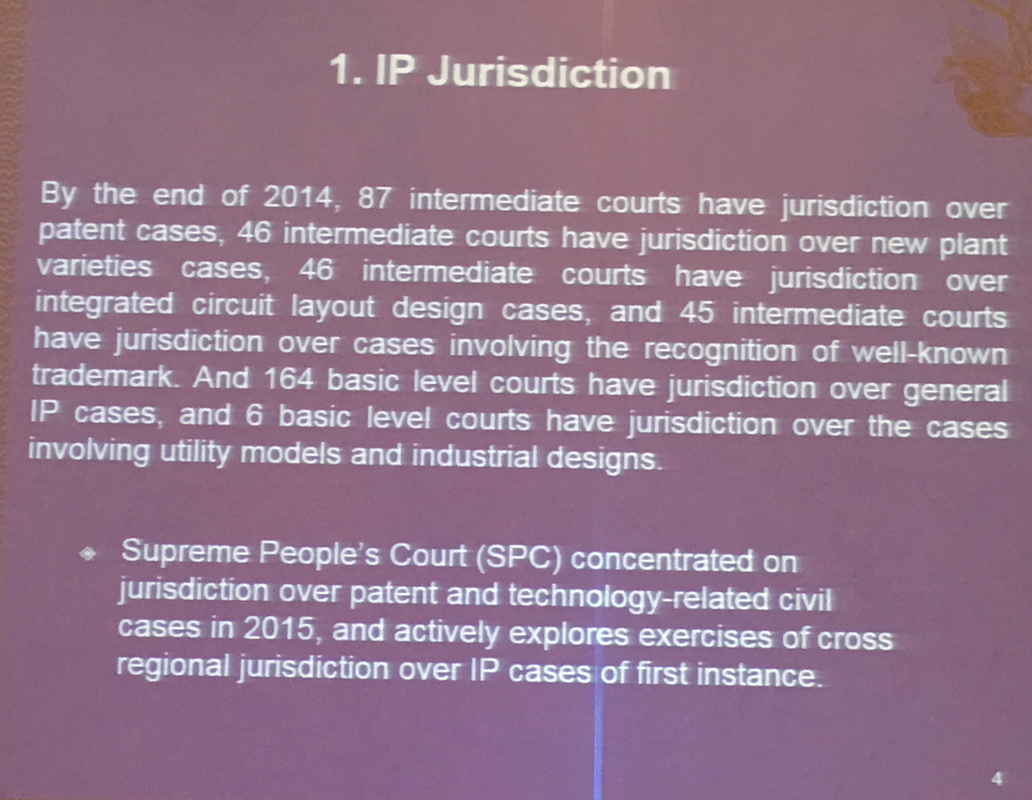

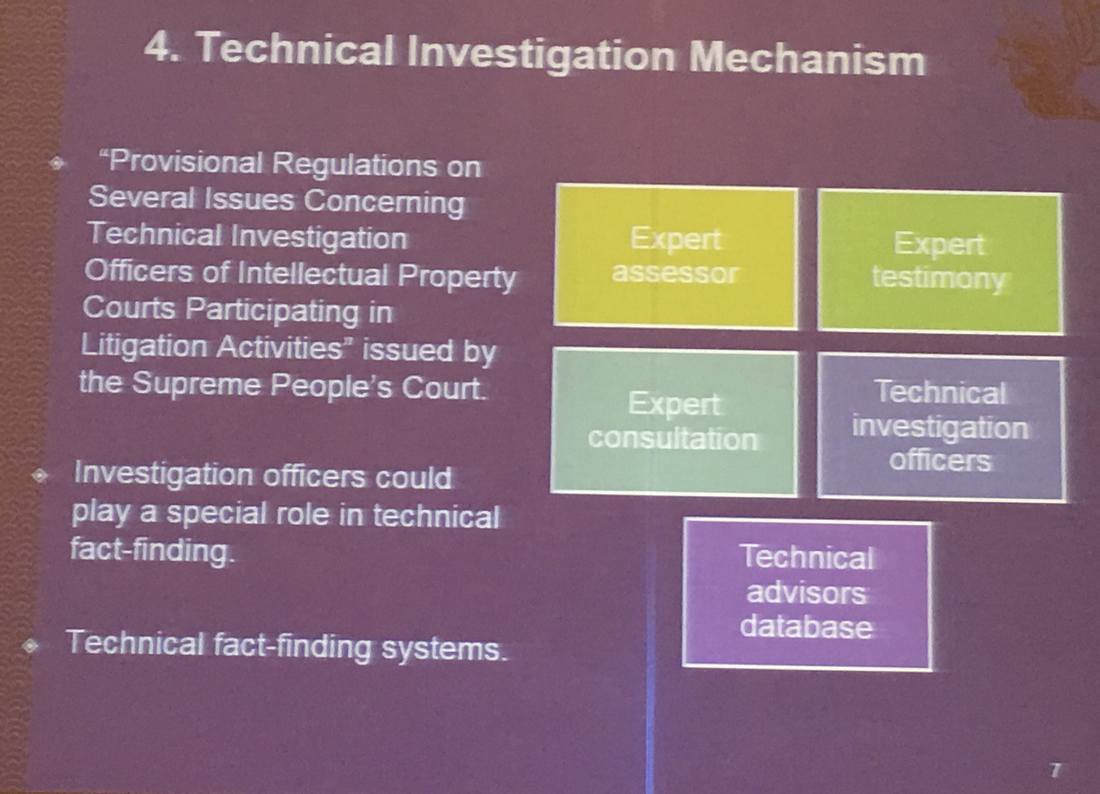

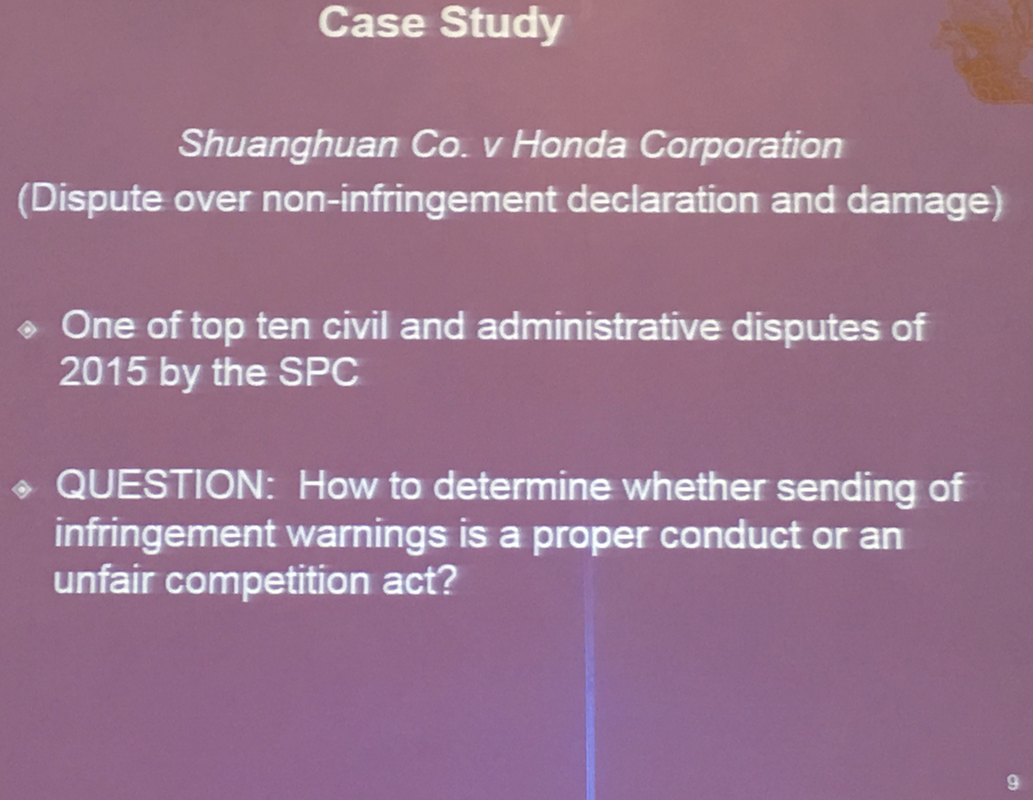

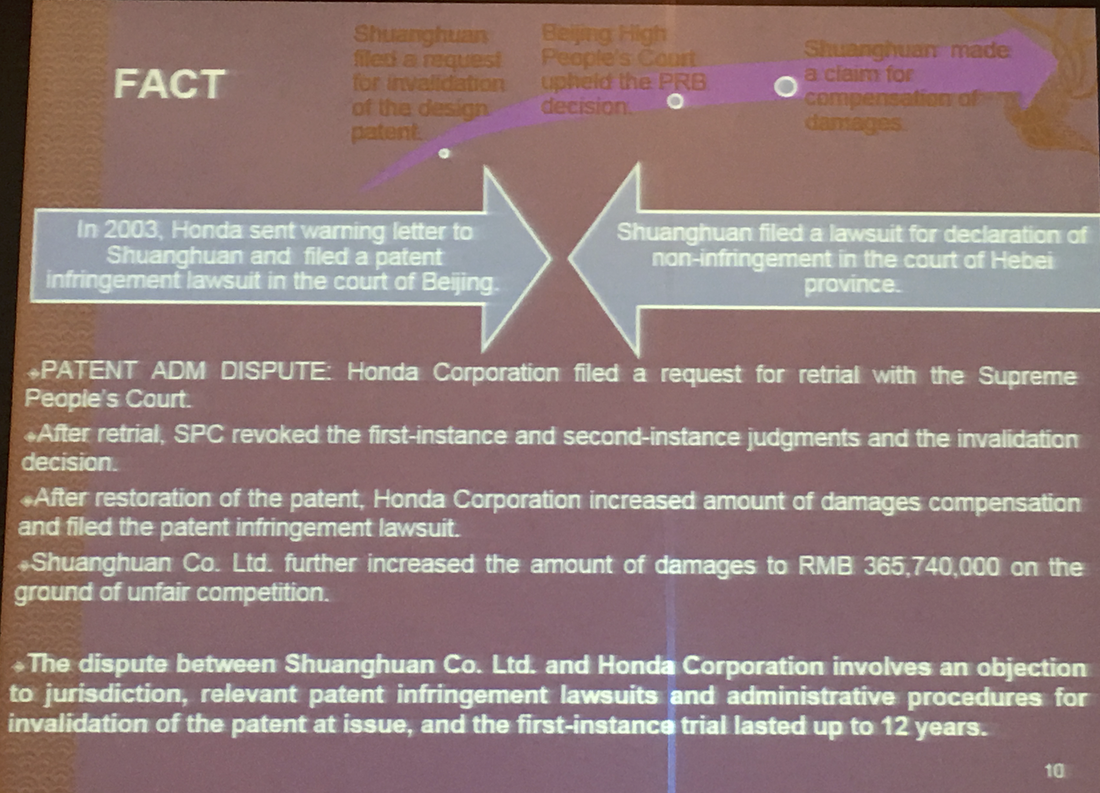

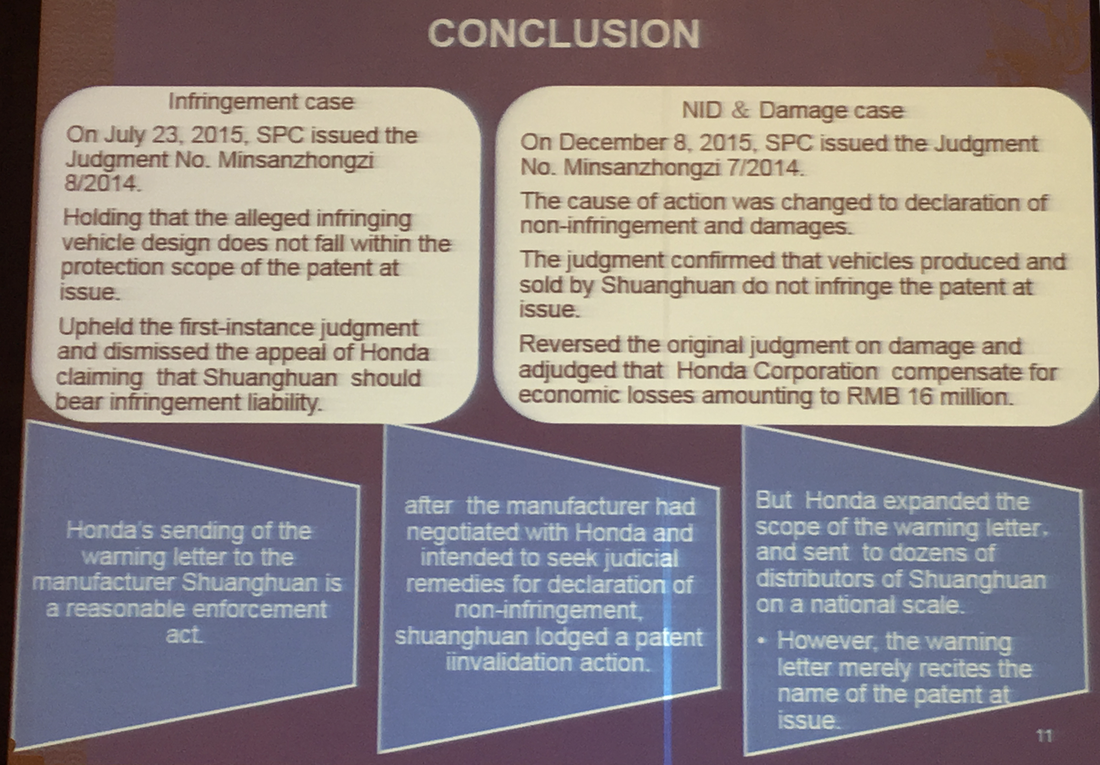

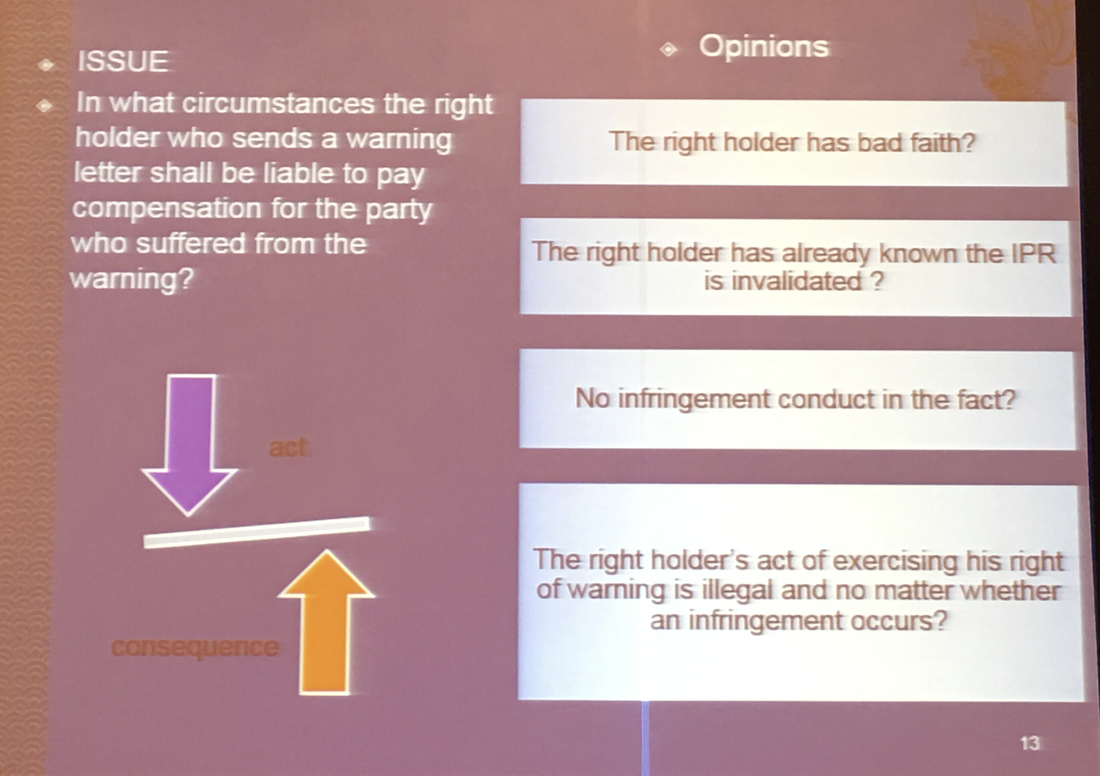

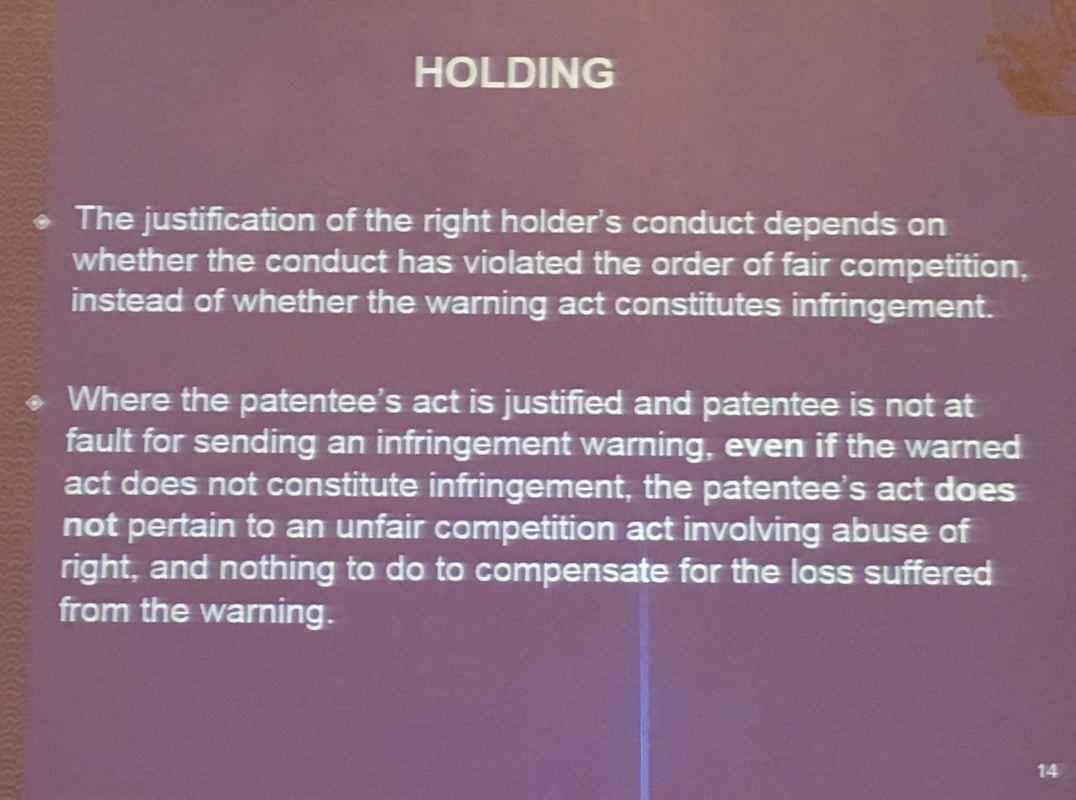

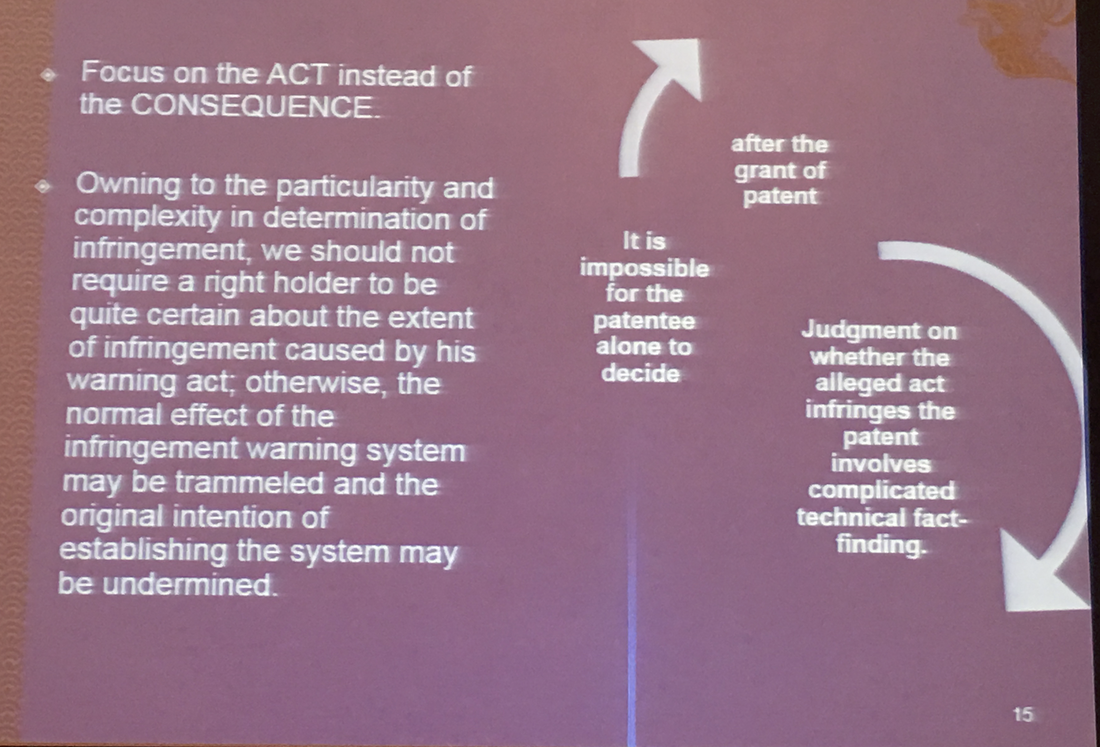

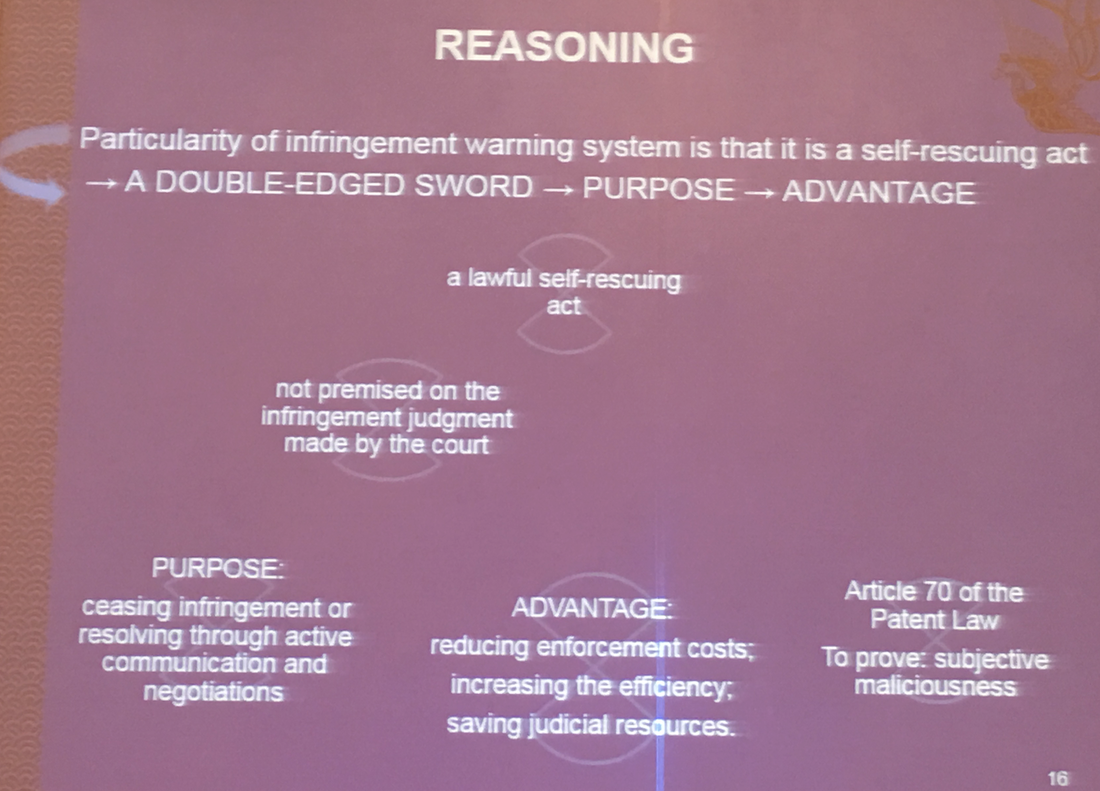

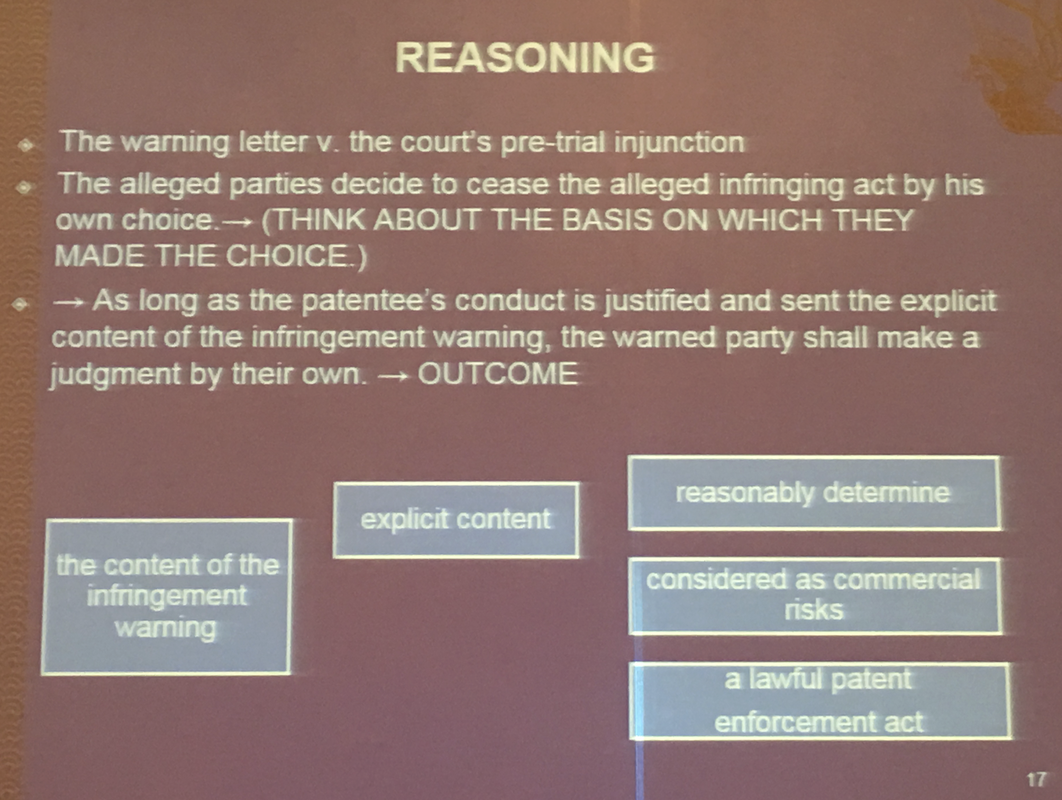

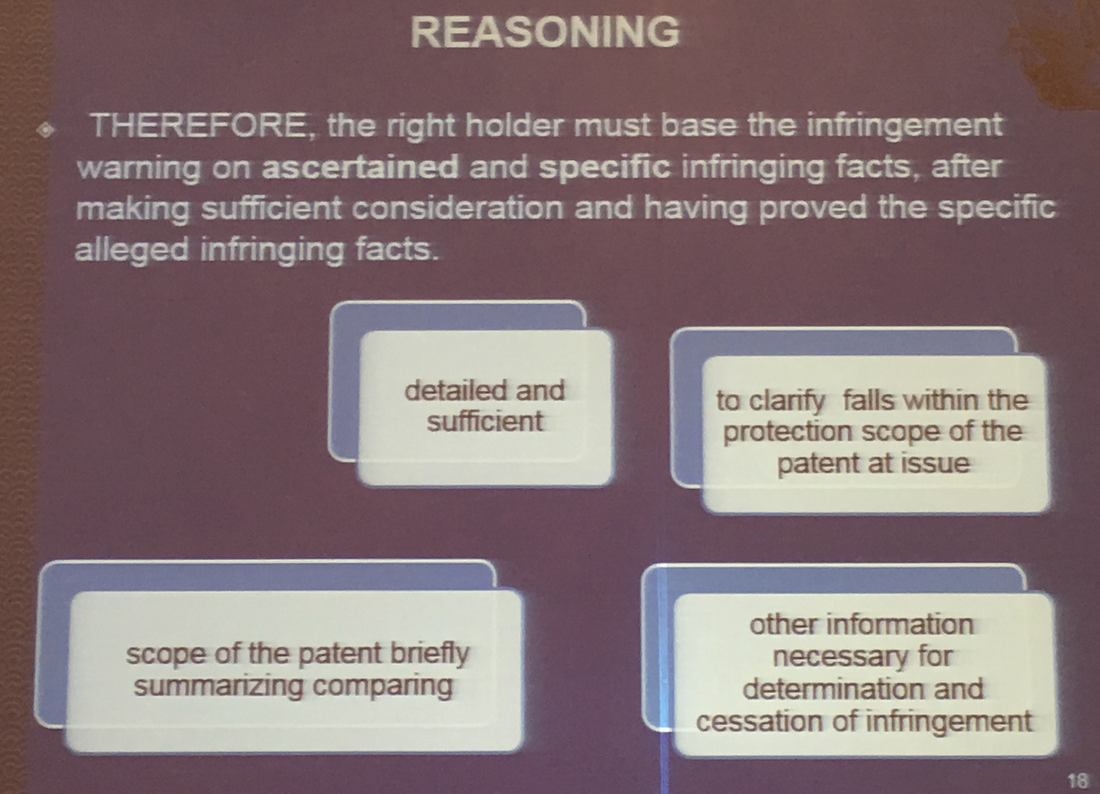

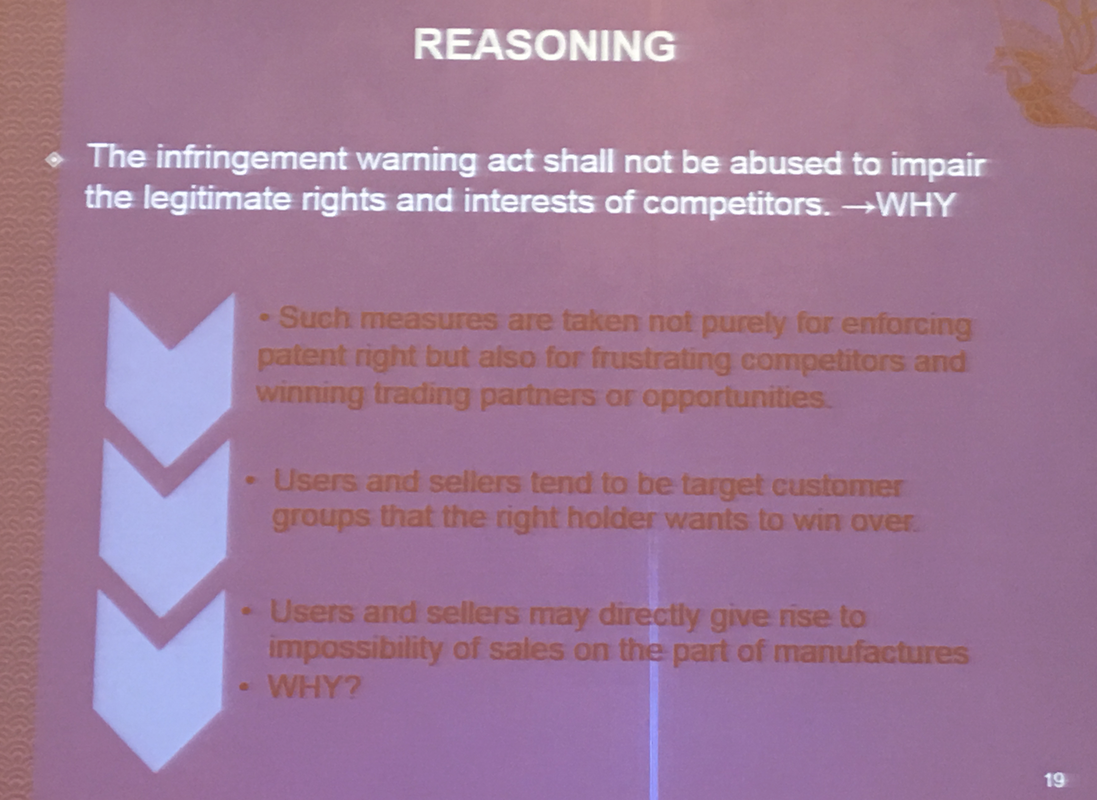

I apologize for not posting in a while but I have been traveling non-stop. A couple of weeks ago I attended the LES (Licensing Executives Society) International Conference in Beijing. It was a great experience meeting so many smart and creative Chinese and international lawyers. Clearly the Chinese legal market is now as hot as the Chinese business market. On Monday, May 16 the Honorable Judge Xia Luo of the Supreme People's Court (the highest court in China) gave the keynote speech. Judge Xia's topic was "China’s Judicial Reforms Are Creating Opportunities for Tech Transfer and Licensing in China". I will provide a summary of what was an interesting and insightful presentation by one of China's leading jurists. Special thanks to Judge Xia for giving me permission to post the slides. Judge Xia was justifiably proud of the Chinese courts' recent improvements in IP enforcement. As slide 3 above shows, the number of foreign IP litigants rose from 2,840 in 2013 to 5,675 in 2015. This comports with my anecdotal findings that foreigners are utilizing the Chinese courts for IP protection, including patent enforcement, significantly more than in the past. However, most cases -- especially patent cases -- are Chinese vs. Chinese litigants. I expect this to change over the next two years. As shown in slide 4 above, as of the end of 2014, 87 intermediate courts have handled patent cases. Intermediate courts are the trial courts in China analogous to the district courts in the United States. The SPC is the highest court in China and is analogous to the U.S. Supreme Court. Judge Xia was particularly proud of the job done by the specialized IP courts in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. By the end of 2015, these courts had handled a combined 15,772 IP cases (including administrative and civil cases). Although certain other courts, particularly those in Shenzhen, handle a lot of IP cases as well, the IP-dedicated courts have changed the paradigm for protecting IP in China. The "3 in 1" concept refers to the fact that IP enforcement can be either civil, administrative, or criminal -- or a combination of the three. It is important to remember that in China extreme cases of patent infringement can be criminal offenses, and this can provide significant leverage for a plaintiff with sufficient proof. Also, in addition to proceeding in the courts through civil patent infringement lawsuits, which are the most robust tool for enforcement, another method is growing much faster: administrative patent enforcement through SIPO and its regional offices. See this IAM Article for more on administrative patent enforcement in China. Something that a lot of foreigners do not realize is that experts can play an important role in Chinese patent litigation. Not only can the litigants hire experts to present findings to the court, but for complicated technical cases, the court will often use their own technical consultants/investigation officers. Obviously the courts' advisers are given more weight than the parties', and in my experience, the only time that a litigant must hire an expert is when it is expected that the litigation opponent will hire one. The result is that they tend to cancel each other out, but if only one side ponies up the money to pay for expert testimony, that can hurt the side lacking such testimony. Also, although experts in the U.S. can cost as much as an entire Chinese litigation, hiring an expert in China is much less expensive. Fees can range from as low as a few thousand dollars to as much as $50,000. But this is often less than one-tenth of what each side pays its experts in American patent cases. IP judgments have been published online sporadically since March 2006 when the SPC launched a website called China IPR Judgments & Decisions, which listed nearly 50,000 judgments and orders by 2013, and over 150,000 by the end of 2015. As of January 1, 2014, the Provisions Concerning the Publication of Judgment and Ruling Documents on the Internet by People’s Courts (最高人民法院关 于人民法院在互联网公布裁判文书的规定) require all final judgments issued by the People’s Courts to be published online. Judges must submit judgments for publication within seven days of the effective date. The China IPR Judgments and Decisions website is available at http://ipr.court.gov.cn/ . Note that this website is in Chinese. Further, the SPC annually releases its top 10 IP judicial protection cases, top 10 innovative cases, and top 50 typical cases. The 2015 cases are available in Chinese (including a version with an automated translation tool) at www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=15689. Although China uses a civil law system, such cases do act as precedent in most cases. Plus, the IP courts and judges increasingly listen to each other and read each others' cases. The result is that most published cases are persuasive, and the larger cases definitely are, despite the fact that they cannot be formally cited. Judge Xia then examined one of the more difficult cases. The case was Shuanghuan Co. v. Honda Corp., and one reported by the SPC as one of the top ten disputes of the year. The issue involved was how to determine whether and when an infringement warning letter is proper and when it constitutes unfair competition. In this slide, Judge Xia set forth the factual details of the case. As the slide notes, the court held that Honda sending a warning letter to the manufacturer was reasonable. But the later act of sending an infringement warning letter to dozens of distributors nationwide was problematic, especially given that the letter gave little information other than providing the patent number which Honda asserted was being infringed. In addition to winning an award for one of the longest patent cases ever heard, the case dealt with many substantive issues. The one that the Judge focused on, though, was the infringement notice letters by Honda. On one side, a patent holder should be able to alert those it believes are infringing the patent. However, if the patent holder casts its net too widely and without proof, then this can constitute unfair competition. Here, the court reasoned that even if the patentee later loses its infringement case, this does not necessarily mean any infringement assertion letters were sent in bad faith, even if there were negative consequences for the accused infringer. That is, if the courts require a patentee to be 100% sure of their infringement assertion and to win any infringement litigation, then there could be no reasonable way for the patentee to protect itself before full adjudication by the court. Indeed, most cases that go to trial, by definition, are close enough to go either way, and are therefore not frivolous. Punishing the patent owner for having the coin turn up on the wrong side is not fair. However, although a patentee's assertion of infringement in a warning letter must not ultimately turn out to be correct based on the court's later judgment, the letter must still be reasonable in terms of scope of both the technology and number of recipients. It must be tailored to prevent infringement of the patent, and not to gain an unfair advantage. Further, the letter must be sufficiently detailed so as to provide enough information for the recipient to understand the allegations and be able to take steps to mitigate, if desired. Determining whether the scope of the letter is reasonable is the most difficult task. One clear rule is that a patentee sending a notice letter lacking sufficient detail so that the recipients can act appropriately based on reasonable knowledge will constitute unfair competition on behalf of the patentee. The same is true if a patentee sends a notice letter to vast numbers of parties too far removed from the facts or acts of infringement. Judge Xia concluded by noting that the world is a much smaller place these days, particularly in the field of IP and patents. China has built an effective system for enforcing patents and other forms of IP and is continuing to improve every day. Just as Western countries and other Asian countries can no longer ignore China based on its economy, technology, and business acumen, these countries can also no longer ignore that China has taken its rightful place at the bargaining table when it comes to intellectual property. All Slides: Leave a Reply. |

Welcome to the China Patent Blog by Erick Robinson. Erick Robinson's China Patent Blog discusses China's patent system and China's surprisingly effective procedures for enforcing patents. China is leading the world in growth in many areas. Patents are among them. So come along with Erick Robinson while he provides a map to the complicated and mysterious world of patents and patent litigation in China.

AuthorErick Robinson is an experienced American trial lawyer and U.S. patent attorney formerly based in Beijing and now based in Texas. He is a Patent Litigation Partner and Co-Chair of the Intellectual Property Practice at Spencer Fane LLP, where he manages patent litigation, licensing, and prosecution in China and the US. Categories

All

Archives

February 2021

Disclaimer: The ideas and opinions at ChinaPatentBlog.com are my own as of the time of posting, have not been vetted with my firm or its clients, and do not necessarily represent the positions of the firm, its lawyers, or any of its clients. None of these posts is intended as legal advice and if you need a lawyer, you should hire one. Nothing in this blog creates an attorney-client relationship. If you make a comment on the post, the comment will become public and beyond your control to change or remove it. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed